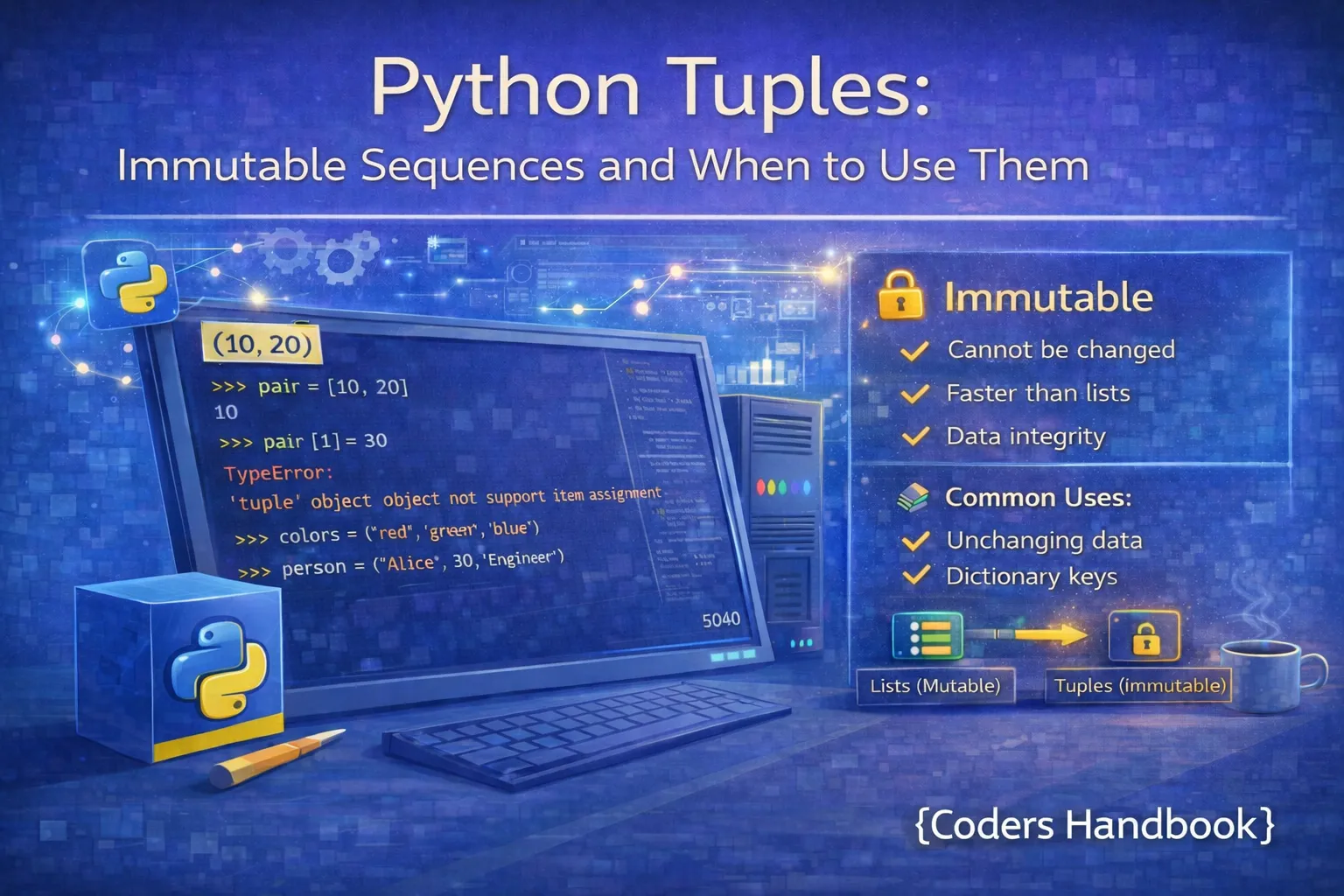

Python Tuples: Immutable Sequences and When to Use Them

Tuples are Python's immutable sequence data structure, representing ordered collections that cannot be modified after creation, making them fundamentally different from lists which allow element changes, additions, and deletions. This immutability provides significant advantages including data integrity guarantees, memory efficiency, hashability for use as dictionary keys, and implicit communication that data should remain constant throughout program execution. Understanding tuples is essential for writing performant Python code, protecting data from accidental modification, working with function return values that bundle multiple items, and choosing the right data structure based on whether mutability is needed or should be prevented.

This comprehensive guide explores tuple creation using parentheses and the tuple() constructor, immutability characteristics and their implications for program design, accessing and slicing tuple elements with indexing operations, tuple packing and unpacking for elegant variable assignment and function returns, the two primary tuple methods count() and index(), performance comparisons demonstrating tuples' memory and speed advantages over lists, practical use cases including function returns and dictionary keys, and decision criteria for choosing tuples versus lists based on mutability requirements. Whether you're optimizing performance-critical code, ensuring data integrity in multi-threaded applications, or returning multiple values from functions, mastering tuples unlocks important Python programming capabilities.

Creating and Understanding Tuples

Tuples are created using parentheses with comma-separated values, though the comma is what actually defines a tuple rather than the parentheses which are often optional except in ambiguous situations. Empty tuples use empty parentheses, single-element tuples require a trailing comma to distinguish them from parenthesized expressions, and the tuple() constructor converts other iterables into tuples. Understanding tuple creation syntax prevents common mistakes like forgetting the trailing comma in single-element tuples or confusing parenthesized expressions with tuple literals.

Tuple Creation Methods

# Tuple Creation Methods

# Basic tuple with parentheses

fruits = ("apple", "banana", "cherry")

numbers = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

print(f"Fruits tuple: {fruits}")

print(f"Numbers tuple: {numbers}")

# Tuple without parentheses (comma defines tuple)

coordinates = 10, 20, 30

print(f"Coordinates: {coordinates}")

print(f"Type: {type(coordinates)}")

# Empty tuple

empty_tuple = ()

print(f"Empty tuple: {empty_tuple}")

# Single element tuple (trailing comma required!)

single_wrong = (5)

single_correct = (5,)

print(f"Without comma: {type(single_wrong)}")

print(f"With comma: {type(single_correct)}")

# Mixed data types

mixed = (1, "hello", 3.14, True, None)

print(f"Mixed types: {mixed}")

# Using tuple() constructor

from_list = tuple([1, 2, 3, 4])

from_string = tuple("Python")

from_range = tuple(range(5))

print(f"From list: {from_list}")

print(f"From string: {from_string}")

print(f"From range: {from_range}")

# Nested tuples

nested = ((1, 2), (3, 4), (5, 6))

print(f"Nested tuple: {nested}")

# Tuple with mutable elements

mixed_tuple = (1, 2, [3, 4])

print(f"Tuple with list: {mixed_tuple}")(5,) creates a tuple, while (5) is just a parenthesized integer. This is one of the most common tuple mistakes for beginners.Understanding Tuple Immutability

Tuple immutability means that once created, you cannot modify, add, or remove elements from the tuple itself. Attempting to change a tuple element raises a TypeError, preventing accidental modifications that could introduce bugs. However, immutability is shallow: if a tuple contains mutable objects like lists or dictionaries, those contained objects can still be modified even though the tuple structure itself remains fixed. This distinction between tuple immutability and contained object mutability is crucial for understanding tuple behavior and avoiding unexpected changes.

Immutability in Action

# Tuple Immutability Examples

# Tuples cannot be modified

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

print(f"Original tuple: {my_tuple}")

# Attempting to modify raises TypeError

try:

my_tuple[0] = 10

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

# Cannot append or extend

try:

my_tuple.append(6)

except AttributeError as e:

print(f"No append method: {e}")

# Cannot delete elements

try:

del my_tuple[0]

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Cannot delete: {e}")

# Comparing with lists (mutable)

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

my_list[0] = 10

print(f"Modified list: {my_list}")

# Shallow immutability: mutable objects inside can change

mixed_tuple = (1, 2, [3, 4])

print(f"Before: {mixed_tuple}")

# The tuple structure is immutable

try:

mixed_tuple[0] = 10

except TypeError:

print("Cannot change tuple element")

# But the list inside CAN be modified

mixed_tuple[2][0] = 30

print(f"After modifying list: {mixed_tuple}")

# Creating new tuples from existing ones

original = (1, 2, 3)

new_tuple = original + (4, 5)

print(f"Original unchanged: {original}")

print(f"New tuple: {new_tuple}")

# Tuple concatenation and repetition

tuple1 = (1, 2)

tuple2 = (3, 4)

combined = tuple1 + tuple2

repeated = ("Hi",) * 3

print(f"Combined: {combined}")

print(f"Repeated: {repeated}")Accessing and Slicing Tuples

Tuple elements are accessed using zero-based indexing with square brackets, supporting both positive indices from the beginning and negative indices from the end just like lists. Slicing operations extract portions of tuples using [start:end:step] syntax, always returning new tuples rather than modifying the original. All standard sequence operations including iteration, membership testing with in, concatenation with +, and repetition with * work identically for tuples as they do for lists, making the syntax familiar while providing immutability guarantees.

# Accessing and Slicing Tuples

fruits = ("apple", "banana", "cherry", "date", "elderberry")

print(f"Tuple: {fruits}")

# Positive indexing

print(f"First: {fruits[0]}")

print(f"Third: {fruits[2]}")

# Negative indexing

print(f"Last: {fruits[-1]}")

print(f"Second last: {fruits[-2]}")

# Slicing operations

numbers = (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

print(f"First three: {numbers[:3]}")

print(f"Middle: {numbers[3:7]}")

print(f"Last three: {numbers[-3:]}")

print(f"Every second: {numbers[::2]}")

print(f"Reversed: {numbers[::-1]}")

# Iteration

print("\nIterating tuple:")

for fruit in fruits:

print(f"- {fruit}")

# Membership testing

if "banana" in fruits:

print("\nBanana found!")

if "grape" not in fruits:

print("Grape not in tuple")

# Tuple length

print(f"\nLength: {len(fruits)}")

# Finding min and max

nums = (45, 23, 67, 12, 89)

print(f"Min: {min(nums)}")

print(f"Max: {max(nums)}")

print(f"Sum: {sum(nums)}")

# Nested tuple access

nested = ((1, 2), (3, 4), (5, 6))

print(f"\nFirst sub-tuple: {nested[0]}")

print(f"Element [1][0]: {nested[1][0]}")Tuple Packing and Unpacking

Tuple packing combines multiple values into a single tuple, while unpacking extracts tuple elements into separate variables in a single assignment statement. This elegant syntax enables returning multiple values from functions, swapping variables without temporary storage, and destructuring complex data structures. Extended unpacking using the asterisk operator collects remaining elements into a list, providing flexible patterns for handling variable-length tuples. Packing and unpacking are among Python's most powerful features, making code more readable and expressive while reducing boilerplate.

Packing and Unpacking Patterns

# Tuple Packing and Unpacking

# Tuple packing (implicit)

packed = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

print(f"Packed tuple: {packed}")

# Tuple unpacking

a, b, c = (10, 20, 30)

print(f"a={a}, b={b}, c={c}")

# Variable swapping without temp variable

x, y = 5, 10

print(f"Before swap: x={x}, y={y}")

x, y = y, x

print(f"After swap: x={x}, y={y}")

# Unpacking with different number causes error

try:

a, b = (1, 2, 3)

except ValueError as e:

print(f"\nError: {e}")

# Extended unpacking with * operator

first, *middle, last = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

print(f"\nFirst: {first}")

print(f"Middle: {middle}")

print(f"Last: {last}")

# * can be in different positions

*start, second_last, last = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

print(f"\nStart: {start}")

print(f"Second last: {second_last}")

print(f"Last: {last}")

# Unpacking in function returns

def get_user_info():

return "Alice", 25, "Engineer"

name, age, profession = get_user_info()

print(f"\nName: {name}, Age: {age}, Job: {profession}")

# Unpacking with underscore for unwanted values

name, _, profession = get_user_info()

print(f"Name: {name}, Job: {profession}")

# Nested unpacking

person = ("Bob", (30, "Designer"))

name, (age, job) = person

print(f"\nName: {name}, Age: {age}, Job: {job}")

# Unpacking in loops

coordinates = [(1, 2), (3, 4), (5, 6)]

print("\nCoordinates:")

for x, y in coordinates:

print(f"x={x}, y={y}")x, y = y, x. This works because the right side creates a tuple before assignment to the left side, eliminating the need for temporary variables.Tuple Methods and Operations

Unlike lists with their extensive collection of methods, tuples provide only two methods: count() for counting element occurrences and index() for finding the first occurrence of a value. This minimal method set reflects tuple immutability since operations like append, remove, and sort would require modification. However, tuples support all standard sequence operations including concatenation, repetition, slicing, and membership testing, plus they can be used with built-in functions like len(), min(), max(), and sum() for aggregate operations.

# Tuple Methods and Operations

fruits = ("apple", "banana", "cherry", "banana", "date")

numbers = (1, 2, 3, 2, 4, 2, 5)

# count() - count occurrences

banana_count = fruits.count("banana")

two_count = numbers.count(2)

print(f"Banana appears: {banana_count} times")

print(f"Number 2 appears: {two_count} times")

# index() - find first occurrence

banana_index = fruits.index("banana")

print(f"First banana at index: {banana_index}")

# index() with start position

second_banana = fruits.index("banana", 2)

print(f"Second banana at index: {second_banana}")

# index() raises ValueError if not found

try:

fruits.index("grape")

except ValueError:

print("Grape not found in tuple")

# Tuple concatenation

tuple1 = (1, 2, 3)

tuple2 = (4, 5, 6)

combined = tuple1 + tuple2

print(f"\nCombined: {combined}")

# Tuple repetition

repeated = ("Python",) * 3

print(f"Repeated: {repeated}")

# Built-in functions

nums = (45, 23, 67, 12, 89, 34)

print(f"\nLength: {len(nums)}")

print(f"Min: {min(nums)}")

print(f"Max: {max(nums)}")

print(f"Sum: {sum(nums)}")

print(f"Sorted: {sorted(nums)}")

# Converting tuple to list (for modification)

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

my_list = list(my_tuple)

my_list.append(4)

new_tuple = tuple(my_list)

print(f"\nOriginal: {my_tuple}")

print(f"Modified as tuple: {new_tuple}")

# Comparing tuples

tuple_a = (1, 2, 3)

tuple_b = (1, 2, 3)

tuple_c = (1, 2, 4)

print(f"\ntuple_a == tuple_b: {tuple_a == tuple_b}")

print(f"tuple_a < tuple_c: {tuple_a < tuple_c}")Performance and Memory Efficiency

Tuples offer significant performance advantages over lists due to their immutability, requiring less memory because they don't need to allocate extra space for potential growth like lists do. Tuple creation and access operations are faster than equivalent list operations, and tuples can be stored in single memory blocks rather than requiring the overhead of dynamic arrays. These performance benefits become noticeable when working with large datasets or performance-critical code, making tuples the preferred choice when data won't be modified after creation.

# Performance Comparison: Tuples vs Lists

import sys

import timeit

# Memory efficiency comparison

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

list_size = sys.getsizeof(my_list)

tuple_size = sys.getsizeof(my_tuple)

print("Memory Usage:")

print(f"List size: {list_size} bytes")

print(f"Tuple size: {tuple_size} bytes")

print(f"Difference: {list_size - tuple_size} bytes")

print(f"Tuple is {((list_size - tuple_size) / list_size * 100):.1f}% smaller")

# Larger data structures

large_list = list(range(1000))

large_tuple = tuple(range(1000))

print(f"\nLarge list: {sys.getsizeof(large_list)} bytes")

print(f"Large tuple: {sys.getsizeof(large_tuple)} bytes")

# Creation time comparison

list_time = timeit.timeit('x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]', number=1000000)

tuple_time = timeit.timeit('x = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)', number=1000000)

print(f"\nCreation Time (1M iterations):")

print(f"List: {list_time:.4f} seconds")

print(f"Tuple: {tuple_time:.4f} seconds")

print(f"Tuple is {((list_time - tuple_time) / list_time * 100):.1f}% faster")

# Access time comparison

test_list = list(range(1000))

test_tuple = tuple(range(1000))

list_access = timeit.timeit('x = test_list[500]',

globals=globals(), number=1000000)

tuple_access = timeit.timeit('x = test_tuple[500]',

globals=globals(), number=1000000)

print(f"\nAccess Time (1M iterations):")

print(f"List: {list_access:.4f} seconds")

print(f"Tuple: {tuple_access:.4f} seconds")When to Use Tuples Over Lists

Choose tuples when data should remain constant throughout program execution, protecting against accidental modifications that could introduce bugs. Tuples work perfectly for returning multiple values from functions, storing heterogeneous data like database records, representing fixed coordinates or configuration values, and serving as dictionary keys since their immutability makes them hashable. Use lists when you need to add, remove, or modify elements after creation, such as maintaining collections that grow dynamically or implementing algorithms requiring in-place modifications.

# Practical Use Cases for Tuples

# Use Case 1: Function returns

def get_min_max(numbers):

"""Return both min and max in one call"""

return min(numbers), max(numbers)

nums = [45, 23, 67, 12, 89]

minimum, maximum = get_min_max(nums)

print(f"Min: {minimum}, Max: {maximum}")

# Use Case 2: Dictionary keys (tuples are hashable)

locations = {

(40.7128, -74.0060): "New York",

(51.5074, -0.1278): "London",

(35.6762, 139.6503): "Tokyo"

}

ny_coords = (40.7128, -74.0060)

print(f"\nCity at {ny_coords}: {locations[ny_coords]}")

# Lists cannot be dictionary keys

try:

invalid_dict = {[1, 2]: "value"}

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Error with list key: {e}")

# Use Case 3: Unpacking database results

def query_user(user_id):

"""Simulate database query"""

return (user_id, "Alice", "[email protected]", 25)

user_id, name, email, age = query_user(101)

print(f"\nUser: {name}, Email: {email}, Age: {age}")

# Use Case 4: Constant configuration

DEFAULT_SETTINGS = (

"localhost",

8080,

"production",

True

)

host, port, environment, debug = DEFAULT_SETTINGS

print(f"\nServer: {host}:{port}, Env: {environment}")

# Use Case 5: Named tuples for structured data

from collections import namedtuple

Point = namedtuple('Point', ['x', 'y'])

p1 = Point(10, 20)

p2 = Point(30, 40)

print(f"\nPoint 1: x={p1.x}, y={p1.y}")

print(f"Point 2: x={p2.x}, y={p2.y}")

# Use Case 6: Protecting data integrity

def process_data(data):

"""Function receives immutable data"""

# Data cannot be accidentally modified

print(f"Processing: {data}")

# Any modification creates new tuple

return data + (100,)

original = (1, 2, 3)

result = process_data(original)

print(f"\nOriginal unchanged: {original}")

print(f"Result: {result}")Best Practices and Decision Guide

Follow these guidelines when deciding between tuples and lists: use tuples for fixed collections that represent single entities like coordinates, RGB colors, or database records where the structure and values shouldn't change. Use lists for collections of similar items that grow or shrink like shopping carts, task lists, or dynamic datasets. Tuples signal to other developers that data is constant and safe to use without defensive copying, while lists indicate mutable collections requiring careful handling. Consider using named tuples from the collections module when tuples have many elements to improve code readability with named fields instead of positional indices.

- Data won't change: Use tuples when values remain constant like coordinates (x, y), RGB colors (r, g, b), or configuration settings that shouldn't be modified during execution

- Dictionary keys: Tuples can be dictionary keys because they're hashable; lists cannot be used as keys due to mutability

- Function returns: Return multiple values as tuples:

return min_val, max_val, avgis cleaner than returning a list or dict - Performance critical: Use tuples in performance-sensitive code or with large datasets where the 15-20% memory savings and faster operations matter

- Data protection: Tuples prevent accidental modification in multi-threaded applications or when passing data to untrusted functions

- Heterogeneous data: Tuples work well for fixed-structure records combining different types like

(id, name, email, age) - Homogeneous collections: Lists better suit collections of similar items like

[task1, task2, task3]that grow or shrink dynamically - Named tuples: Use

namedtuplefor tuples with many elements to access fields by name instead of index:point.xvspoint[0]

Conclusion

Python tuples provide immutable sequence data structures offering significant advantages over lists including data integrity guarantees preventing accidental modifications, memory efficiency with approximately 15-20% smaller footprint, faster creation and access operations, and hashability enabling use as dictionary keys and set elements. Tuple creation uses parentheses with comma-separated values, though commas define tuples rather than parentheses, and single-element tuples require trailing commas to distinguish them from parenthesized expressions. Immutability means tuple elements cannot be changed after creation, though shallow immutability allows contained mutable objects to be modified while the tuple structure remains fixed. Accessing and slicing tuples works identically to lists using zero-based indexing and slice notation, supporting all standard sequence operations including iteration, membership testing, concatenation, and repetition.

Tuple packing and unpacking provide elegant syntax for combining values into tuples and extracting elements into variables, enabling powerful patterns including returning multiple values from functions, swapping variables without temporary storage, and destructuring complex data with extended unpacking using asterisk operators. The minimal method set containing only count() and index() reflects immutability constraints while supporting all standard sequence operations and built-in functions for aggregate computations. Performance benchmarks demonstrate tuples' advantages in memory usage and execution speed, making them optimal for large datasets or performance-critical code. Use tuples for fixed collections representing single entities like coordinates or database records, function return values bundling multiple items, dictionary keys requiring hashability, and situations where data protection prevents accidental modification. Choose lists when collections need dynamic growth, modification methods, or in-place algorithms. By understanding tuple characteristics, immutability implications, packing and unpacking patterns, performance benefits, and appropriate use cases, you gain the knowledge to choose the right data structure based on mutability requirements, optimize application performance, protect data integrity, and write more expressive Python code leveraging tuples' unique capabilities.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!