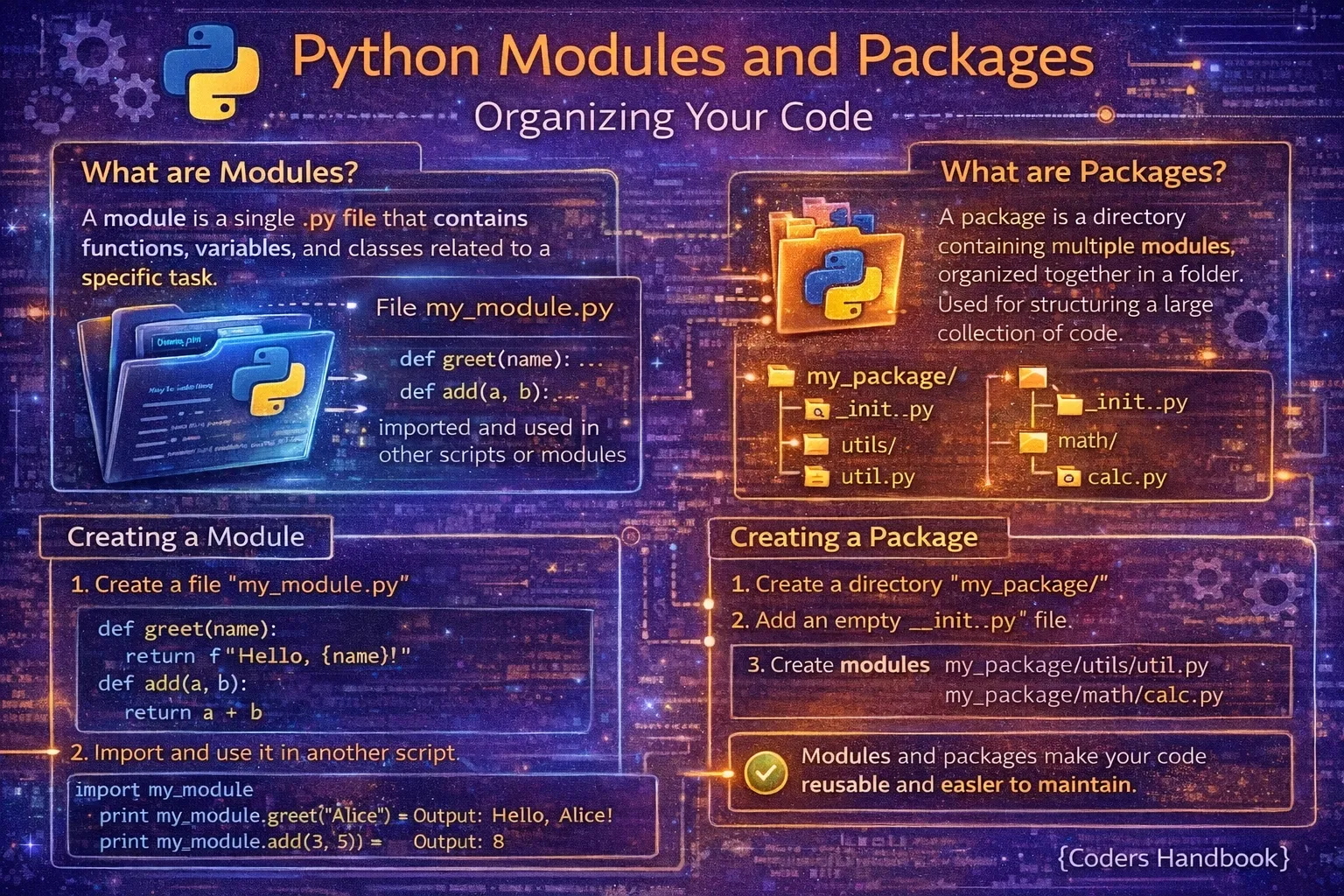

Python Modules and Packages: Organizing Your Code

Modules and packages are Python's fundamental mechanisms for organizing code into reusable, maintainable components that promote separation of concerns and enable code sharing across projects. A module is simply a Python file containing definitions and statements, while a package is a directory containing multiple modules organized hierarchically with a special __init__.py file marking it as a package. Understanding modules and packages is essential for building scalable applications, as they prevent code duplication through reusability, improve maintainability by organizing related functionality together, enable namespace management avoiding naming conflicts, and facilitate team collaboration by allowing developers to work on separate modules independently.

This comprehensive guide explores creating custom modules by saving Python files and importing them, various import statement forms including standard imports, from imports, aliasing with as, and wildcard imports, package creation using directory structures and __init__.py files controlling package initialization and exports, relative versus absolute imports for navigating package hierarchies, Python's standard library modules providing built-in functionality, best practices for organizing project structures with logical separation, and common pitfalls including circular imports and namespace pollution. Whether you're building small scripts requiring utility functions, web applications with organized route handlers and database models, data science projects with separate analysis and visualization modules, or libraries distributed to other developers, mastering modules and packages provides the organizational foundation for professional Python development enabling clean, maintainable, and scalable code architecture.

Creating and Importing Modules

A module is any Python file with a .py extension containing functions, classes, and variables that can be imported into other Python files. Creating a module is as simple as saving code in a file, while importing makes that code available elsewhere using import statements. Module names should follow Python naming conventions using lowercase with underscores, avoiding names that conflict with standard library modules or Python keywords.

# Creating a Module: math_utils.py

# Save this code in a file named 'math_utils.py'

"""Math utility functions."""

def add(a, b):

"""Add two numbers."""

return a + b

def multiply(a, b):

"""Multiply two numbers."""

return a * b

def factorial(n):

"""Calculate factorial of n."""

if n <= 1:

return 1

return n * factorial(n - 1)

PI = 3.14159

class Calculator:

"""Simple calculator class."""

@staticmethod

def divide(a, b):

if b == 0:

raise ValueError("Cannot divide by zero")

return a / b

# This code runs when module is executed directly

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Running math_utils module directly")

print(f"5! = {factorial(5)}")

# Using the Module: main.py

# Save this in a different file in the same directory

# Method 1: Import entire module

import math_utils

result = math_utils.add(5, 3)

print(result) # Output: 8

print(math_utils.PI) # Output: 3.14159

calc = math_utils.Calculator()

print(calc.divide(10, 2)) # Output: 5.0

# Method 2: Import specific items

from math_utils import add, multiply, PI

result = add(10, 20)

print(result) # Output: 30

print(PI) # Output: 3.14159

# Method 3: Import with alias

import math_utils as mu

result = mu.multiply(4, 5)

print(result) # Output: 20

# Method 4: Import specific with alias

from math_utils import factorial as fact

result = fact(6)

print(result) # Output: 720

# Method 5: Import everything (not recommended)

from math_utils import *

result = add(1, 2) # No prefix needed

print(result) # Output: 3if __name__ == '__main__': only runs when the file is executed directly, not when imported. Use this for testing code or demo usage without affecting imports.Import Statement Variations

Python provides multiple import forms each serving different purposes: standard import module requiring full qualification, from module import item bringing specific names into namespace, import module as alias for shorter references, and from module import * importing everything though discouraged for namespace pollution. Understanding when to use each form enables writing clear, maintainable import statements that balance convenience with explicitness.

# Import Statement Variations

# 1. Standard import (explicit, recommended)

import math

import datetime

result = math.sqrt(16)

print(result) # Output: 4.0

now = datetime.datetime.now()

print(now)

# 2. From import (selective, clear)

from math import sqrt, pi, cos

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

result = sqrt(25)

print(result) # Output: 5.0

print(pi) # Output: 3.141592653589793

tomorrow = datetime.now() + timedelta(days=1)

print(tomorrow)

# 3. Import with alias (common for long names)

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Now use short aliases

array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

df = pd.DataFrame({'col': [1, 2, 3]})

# 4. From import with alias

from collections import defaultdict as dd

from datetime import datetime as dt

my_dict = dd(list)

current = dt.now()

# 5. Multiple imports from same module

from os import path, listdir, getcwd

from sys import argv, exit, path as sys_path

print(getcwd())

print(sys_path)

# 6. Wildcard import (AVOID in production)

from math import *

# Everything from math is now available

result = sqrt(9) + sin(0) + cos(0)

print(result) # Output: 4.0

# Problems with wildcard:

# - Unclear what names are imported

# - Can overwrite existing names

# - Makes code harder to maintain

# 7. Import in function (lazy loading)

def process_data():

import json # Only imported when function called

data = json.loads('{"key": "value"}')

return data

# 8. Conditional imports

try:

import numpy as np

HAS_NUMPY = True

except ImportError:

HAS_NUMPY = False

print("NumPy not available")

if HAS_NUMPY:

# Use numpy functionality

passfrom module import * pollutes namespace, makes code unclear (where do names come from?), and can cause name collisions. Use explicit imports for maintainable code.Creating Python Packages

Packages organize related modules into directory hierarchies, creating namespaces that prevent naming conflicts and group functionality logically. A directory becomes a package when it contains an __init__.py file, which can be empty or contain initialization code and control what's exported. Package structures support nested packages for complex applications, enabling organization like myapp.database.models or myapp.web.routes mirroring application architecture.

# Creating a Package Structure

# Directory structure:

# mypackage/

# __init__.py

# module1.py

# module2.py

# subpackage/

# __init__.py

# module3.py

# File: mypackage/__init__.py

"""My package for demonstration."""

# Package-level variables

VERSION = "1.0.0"

# Import commonly used items to package level

from .module1 import function1

from .module2 import Class2

# Control what's exported with wildcard import

__all__ = ['function1', 'Class2', 'VERSION']

print("mypackage initialized")

# File: mypackage/module1.py

"""Module 1 of mypackage."""

def function1():

"""Public function."""

return "Function 1 from module1"

def _private_function():

"""Private function (convention: starts with _)."""

return "This is private"

class Class1:

"""Class from module1."""

pass

# File: mypackage/module2.py

"""Module 2 of mypackage."""

def function2():

return "Function 2 from module2"

class Class2:

"""Class from module2."""

def method(self):

return "Method from Class2"

# File: mypackage/subpackage/__init__.py

"""Subpackage of mypackage."""

from .module3 import function3

# File: mypackage/subpackage/module3.py

"""Module 3 in subpackage."""

def function3():

return "Function 3 from subpackage"

# Using the Package: main.py

# Import entire package

import mypackage

result = mypackage.function1()

print(result) # Output: Function 1 from module1

obj = mypackage.Class2()

print(obj.method()) # Output: Method from Class2

print(mypackage.VERSION) # Output: 1.0.0

# Import specific module

import mypackage.module1

result = mypackage.module1.function1()

print(result)

# Import from subpackage

from mypackage.subpackage import function3

result = function3()

print(result) # Output: Function 3 from subpackage

# Import with full path

from mypackage.subpackage.module3 import function3

result = function3()

print(result)Understanding __init__.py

The __init__.py file serves multiple purposes: marking directories as packages, executing initialization code when packages are imported, controlling package-level exports through __all__, and providing convenient access to nested modules by importing them at package level. While Python 3.3+ allows implicit namespace packages without __init__.py, explicit init files remain best practice for clarity and control over package behavior.

# __init__.py Examples

# Example 1: Empty __init__.py

# Minimal approach - just marks directory as package

# mypackage/__init__.py (empty file)

# Example 2: Initialization code

# mypackage/__init__.py

"""Package with initialization."""

import logging

# Set up package-level logger

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.info("Package initialized")

# Package constants

VERSION = "2.0.0"

AUTHOR = "Your Name"

# Example 3: Convenient imports

# mypackage/__init__.py

"""Package exposing commonly used items."""

# Import from submodules to package level

from .database import connect, Query

from .utils import format_data, validate

from .models import User, Product

# Now users can do:

# from mypackage import User, connect

# instead of:

# from mypackage.models import User

# from mypackage.database import connect

# Example 4: Controlling exports with __all__

# mypackage/__init__.py

"""Package controlling wildcard imports."""

from .module1 import func1, func2

from .module2 import Class1, Class2

# Only these are exported with 'from mypackage import *'

__all__ = [

'func1',

'Class1',

'VERSION'

]

VERSION = "1.0.0"

# func2 and Class2 are still accessible but not exported

# Example 5: Package initialization with setup

# mypackage/__init__.py

"""Package with setup on import."""

import os

import sys

# Check dependencies

try:

import numpy

except ImportError:

print("Warning: NumPy not installed")

# Set package paths

PACKAGE_DIR = os.path.dirname(__file__)

DATA_DIR = os.path.join(PACKAGE_DIR, 'data')

# Add package resources

if DATA_DIR not in sys.path:

sys.path.insert(0, DATA_DIR)

# Initialize package resources

def _init_resources():

"""Initialize package resources."""

if not os.path.exists(DATA_DIR):

os.makedirs(DATA_DIR)

_init_resources()

# Example 6: Lazy imports for performance

# mypackage/__init__.py

"""Package with lazy loading."""

def get_heavy_module():

"""Import heavy module only when needed."""

from . import heavy_module

return heavy_module

# Only imported when function is called

# Faster package import time__init__.py to provide convenient imports of commonly used items, define package metadata (version, author), and initialize resources. Keep it lightweight to maintain fast import times.Relative vs Absolute Imports

Absolute imports specify the full path from the project root, making code portable and clear about dependencies, while relative imports use dots to navigate the package hierarchy enabling flexible reorganization and avoiding hard-coded package names. Relative imports using single dots for current package and double dots for parent packages work only within packages, not in standalone scripts. PEP 8 recommends absolute imports for clarity, with relative imports acceptable for intra-package references.

# Relative vs Absolute Imports

# Package structure:

# myproject/

# __init__.py

# app/

# __init__.py

# models/

# __init__.py

# user.py

# product.py

# views/

# __init__.py

# user_view.py

# utils/

# __init__.py

# helpers.py

# File: myproject/app/models/user.py

"""User model."""

class User:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# File: myproject/app/utils/helpers.py

"""Helper functions."""

def format_name(name):

return name.upper()

# File: myproject/app/views/user_view.py

"""User view using different import styles."""

# ABSOLUTE IMPORTS (Recommended for clarity)

from myproject.app.models.user import User

from myproject.app.utils.helpers import format_name

def display_user():

user = User("Alice")

formatted = format_name(user.name)

return formatted

# RELATIVE IMPORTS (Good for intra-package)

# Same file with relative imports:

# Import from sibling package (models is sibling to views)

from ..models.user import User

# Import from another sibling package (utils)

from ..utils.helpers import format_name

# Import from current package

from . import some_module

# Import from parent package

from .. import some_parent_module

# Relative import examples:

# .module - Same package

# ..module - Parent package

# ..sibling.module - Sibling package

# ...module - Grandparent package

# File: myproject/app/models/product.py

"""Product model with imports."""

# Absolute import (clear, portable)

from myproject.app.models.user import User

# Relative import (flexible)

from .user import User

class Product:

def __init__(self, name, owner):

self.name = name

self.owner = owner # User instance

# Relative imports ONLY work in packages

# This WON'T work in standalone scripts:

# python user_view.py # Error!

# Must run as module:

# python -m myproject.app.views.user_view # Works!

# Comparison table:

# Absolute: from myproject.app.models import User

# Relative: from ..models import User

# Absolute advantages:

# - Clear where imports come from

# - Work in any context

# - Easier to search/grep

# - Better IDE support

# Relative advantages:

# - Package can be renamed easily

# - Shorter for deep hierarchies

# - Clear intra-package relationshipsProject Structure Best Practices

Well-organized project structures separate concerns into logical packages, group related functionality, and follow established conventions making projects easier to navigate and maintain. Common patterns include separating application code from tests, configuration files, documentation, and data, using clear naming conventions, and structuring packages by feature or layer depending on application architecture.

# Recommended Project Structure

# Small Project:

# myproject/

# README.md

# requirements.txt

# setup.py

# myproject/

# __init__.py

# main.py

# utils.py

# tests/

# __init__.py

# test_main.py

# test_utils.py

# Medium Project (Feature-based):

# myapp/

# README.md

# requirements.txt

# setup.py

# myapp/

# __init__.py

# config.py

# main.py

# users/

# __init__.py

# models.py

# views.py

# services.py

# products/

# __init__.py

# models.py

# views.py

# common/

# __init__.py

# utils.py

# exceptions.py

# tests/

# test_users.py

# test_products.py

# docs/

# api.md

# Large Project (Layer-based):

# webapp/

# README.md

# requirements.txt

# setup.py

# webapp/

# __init__.py

# config/

# __init__.py

# settings.py

# database.py

# models/

# __init__.py

# user.py

# product.py

# services/

# __init__.py

# user_service.py

# product_service.py

# api/

# __init__.py

# routes.py

# schemas.py

# utils/

# __init__.py

# helpers.py

# validators.py

# tests/

# unit/

# test_models.py

# test_services.py

# integration/

# test_api.py

# migrations/

# static/

# templates/

# scripts/

# init_db.py

# File: setup.py (for package distribution)

from setuptools import setup, find_packages

setup(

name='myproject',

version='1.0.0',

packages=find_packages(),

install_requires=[

'requests>=2.25.0',

'numpy>=1.19.0',

],

python_requires='>=3.8',

)

# File: requirements.txt

# requests==2.28.0

# numpy==1.24.0

# pytest==7.2.0Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

- Use absolute imports: Prefer

from myproject.module import funcover relative imports for clarity and portability, especially in larger projects - Avoid circular imports: Don't have module A import module B while B imports A. Restructure code or use local imports inside functions

- Organize by feature or layer: Group related functionality together. Feature-based for smaller apps, layer-based for larger architectures

- Keep __init__.py lightweight: Heavy initialization slows imports. Use lazy loading for expensive resources

- Don't use wildcard imports:

from module import *pollutes namespace and makes code unclear. Import explicitly - Follow naming conventions: Packages/modules use lowercase_with_underscores. Avoid names conflicting with standard library

- Document package structure: Include README explaining package organization and how modules relate to each other

- Use __all__ for exports: Define

__all__in modules/packages to control what's exported with wildcard imports - Separate concerns: Keep models, views, utilities, tests, and configuration in distinct modules or packages

- Test your imports: Ensure modules can be imported from expected locations. Use

if __name__ == '__main__'for test code

Conclusion

Python modules and packages provide essential mechanisms for organizing code into reusable, maintainable components with modules being Python files containing definitions and packages being directories with __init__.py files organizing modules hierarchically. Creating modules is as simple as saving Python code in files and importing using various forms including standard import module requiring full qualification, from module import item bringing specific names into namespace, import module as alias for convenient references, and from module import * wildcard imports discouraged for namespace pollution. Package creation involves directory structures with __init__.py files marking directories as packages, executing initialization code controlling package behavior, defining __all__ for export control, and providing convenient access to nested modules by importing them at package level for user convenience.

Relative imports using dots navigate package hierarchies with single dots for current packages and double dots for parents, working only within packages and enabling flexible reorganization, while absolute imports specify full paths from project roots providing clarity and portability with PEP 8 recommending absolutes for explicitness. Project structure best practices separate concerns into logical packages organizing by features for smaller applications or layers for larger architectures, following naming conventions using lowercase with underscores, documenting structure in README files, and maintaining clean separation between application code, tests, configuration, and resources. Common pitfalls include circular imports where modules depend on each other requiring restructuring or local imports, wildcard imports polluting namespaces and obscuring origins, heavy __init__.py files slowing imports requiring lazy loading, and naming conflicts with standard library modules causing subtle bugs. Best practices emphasize preferring absolute imports for clarity, avoiding circular dependencies through careful design, organizing code logically by feature or layer, keeping initialization lightweight, using explicit imports over wildcards, following Python naming conventions, documenting package organization, defining __all__ for controlled exports, separating concerns into distinct modules, and testing import paths ensure packages work as expected. By mastering module creation and importing, package organization with __init__.py, import statement variations balancing convenience with clarity, relative versus absolute import trade-offs, project structure patterns supporting scalability, and best practices avoiding common pitfalls, you gain essential organizational skills for building professional Python applications with clean, maintainable, and scalable code architecture enabling effective team collaboration and long-term project evolution.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!