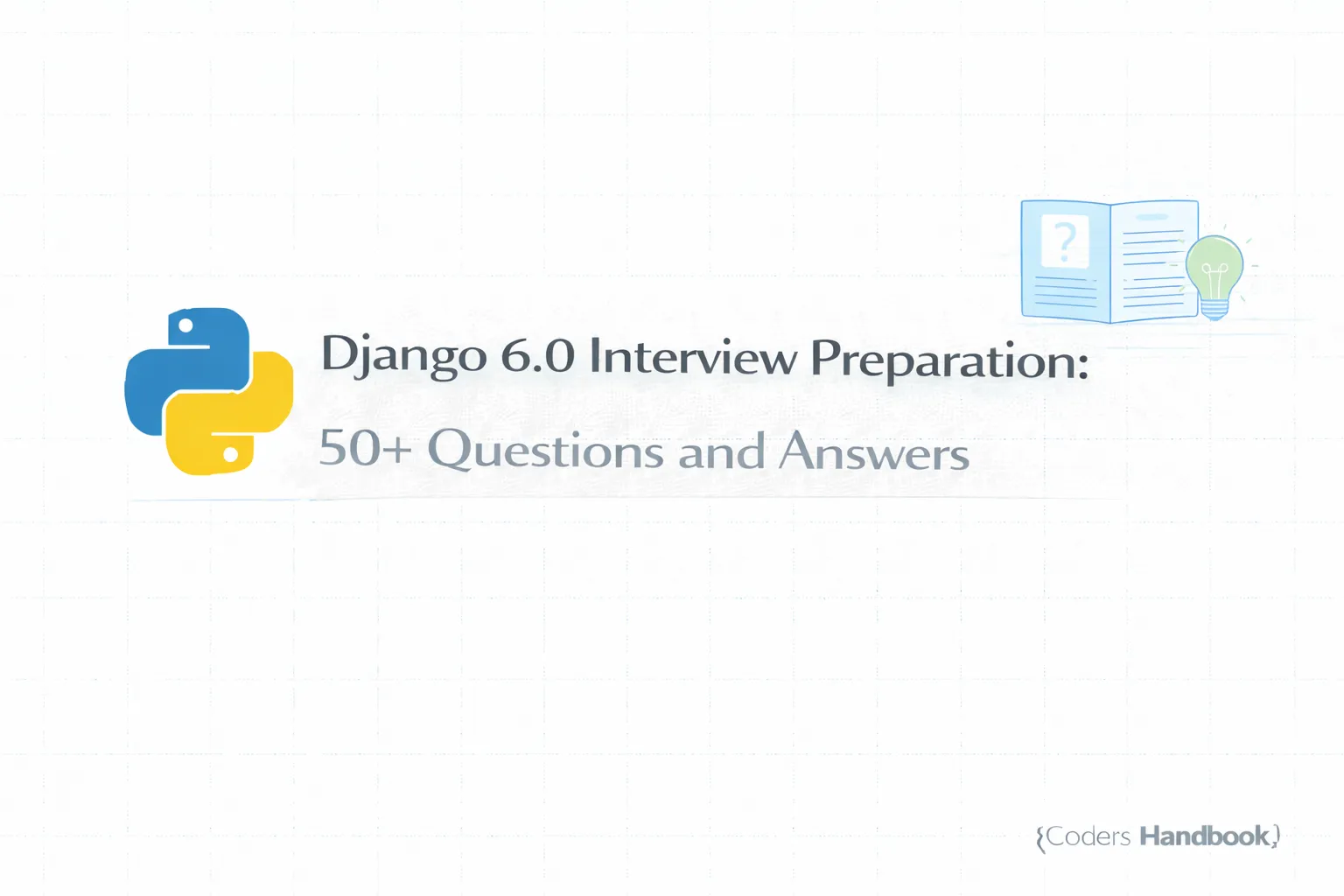

Python Functions: Creating Reusable and Modular Code

Functions are fundamental building blocks in Python programming, enabling code reusability by encapsulating logic that can be called multiple times with different inputs, reducing duplication, improving maintainability, and organizing programs into logical, modular components. Python functions are defined using the def keyword followed by function name, parameters in parentheses, and an indented code block containing the function body, with optional return statements sending values back to callers. Understanding functions is essential for writing professional Python code, as they enable abstraction of complex operations, facilitate testing by isolating functionality, support code reuse across projects, and implement the Don't Repeat Yourself principle fundamental to clean code practices.

This comprehensive guide explores function definition syntax and calling conventions, parameters and arguments including positional and keyword forms, return values for sending results back to callers, default arguments providing optional parameters with fallback values, keyword arguments enabling named parameter passing, variable-length arguments using *args and **kwargs for flexible parameter counts, function scope and variable visibility including local versus global scope, lambda functions for anonymous single-expression functions, and best practices for writing clear, maintainable, and well-documented functions. Whether you're building utility libraries with reusable helper functions, web applications with modular route handlers, data processing pipelines with transformation functions, or automation scripts with task-specific operations, mastering Python functions unlocks the ability to write organized, maintainable, and professional code following established software engineering principles.

Function Definition and Calling

Functions are defined using the def keyword followed by the function name, parentheses containing parameters, a colon, and an indented code block forming the function body. Function names should follow snake_case convention and describe the action performed, parameters define inputs the function accepts, and the return statement sends values back to the caller, with functions returning None implicitly if no return statement is provided. Calling functions involves using the function name followed by parentheses containing arguments matching the defined parameters.

# Basic Function Definition and Calling

# Function with no parameters

def greet():

"""Print a greeting message."""

print("Hello, World!")

greet() # Output: Hello, World!

# Function with parameters

def greet_person(name):

"""Greet a specific person."""

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

greet_person("Alice") # Output: Hello, Alice!

# Function with return value

def add(a, b):

"""Add two numbers and return the result."""

return a + b

result = add(5, 3)

print(result) # Output: 8

# Function with multiple parameters

def calculate_area(length, width):

"""Calculate rectangle area."""

area = length * width

return area

rect_area = calculate_area(10, 5)

print(f"Area: {rect_area}") # Output: Area: 50

# Function returning multiple values (as tuple)

def get_min_max(numbers):

"""Return minimum and maximum from list."""

return min(numbers), max(numbers)

minimum, maximum = get_min_max([3, 7, 1, 9, 2])

print(f"Min: {minimum}, Max: {maximum}") # Output: Min: 1, Max: 9

# Function with no return (implicitly returns None)

def print_message(msg):

"""Print a message."""

print(msg)

result = print_message("Test")

print(result) # Output: None

# Function with early return

def is_positive(number):

"""Check if number is positive."""

if number > 0:

return True

return False

print(is_positive(5)) # Output: True

print(is_positive(-3)) # Output: Falsereturn statement return None. Use return to send values back to callers. You can return multiple values as a tuple using comma separation: return a, b, c.Parameters and Arguments

Parameters are variables defined in function signatures that receive values when functions are called, while arguments are actual values passed during function calls. Python supports positional arguments matching parameters by order, keyword arguments matching parameters by name enabling reordering and clarity, and combinations of both following the rule that positional arguments must precede keyword arguments. Understanding parameter-argument relationships enables flexible function interfaces accommodating various calling styles while maintaining code readability.

# Parameters and Arguments

# Positional arguments (order matters)

def introduce(name, age, city):

"""Introduce a person."""

print(f"{name} is {age} years old from {city}")

introduce("Alice", 25, "NYC") # Output: Alice is 25 years old from NYC

# Keyword arguments (order doesn't matter)

introduce(city="Boston", name="Bob", age=30)

# Output: Bob is 30 years old from Boston

# Mixed positional and keyword arguments

introduce("Charlie", age=28, city="Chicago")

# Output: Charlie is 28 years old from Chicago

# Error: keyword argument before positional

# introduce(name="Diana", 32, "Denver") # SyntaxError!

# Positional arguments must come first

introduce("Eve", 27, city="LA")

# Output: Eve is 27 years old from LA

# Function with many parameters

def create_user(username, email, age, city, country):

"""Create user profile."""

return {

"username": username,

"email": email,

"age": age,

"city": city,

"country": country

}

# Using keyword arguments for clarity

user = create_user(

username="john_doe",

email="[email protected]",

age=30,

city="NYC",

country="USA"

)

print(user)

# Argument unpacking with *

values = ["Alice", 25, "NYC"]

introduce(*values) # Unpacks list as positional arguments

# Argument unpacking with **

user_data = {"name": "Bob", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

introduce(**user_data) # Unpacks dict as keyword argumentsDefault Arguments

Default arguments provide fallback values for parameters when callers don't supply arguments, making parameters optional and enabling flexible function interfaces. Defined by assigning values in function signatures using =, default parameters must follow non-default parameters to avoid ambiguity. Default values are evaluated once when the function is defined, creating a subtle gotcha with mutable defaults like lists or dictionaries that persist across calls, requiring the idiom of using None as default and creating new mutable objects inside the function.

# Default Arguments

# Basic default argument

def greet(name, greeting="Hello"):

"""Greet with optional custom greeting."""

print(f"{greeting}, {name}!")

greet("Alice") # Output: Hello, Alice!

greet("Bob", "Hi") # Output: Hi, Bob!

greet("Charlie", greeting="Hey") # Output: Hey, Charlie!

# Multiple default arguments

def create_profile(name, age=18, city="Unknown", active=True):

"""Create user profile with defaults."""

return {

"name": name,

"age": age,

"city": city,

"active": active

}

print(create_profile("Alice"))

# Output: {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 18, 'city': 'Unknown', 'active': True}

print(create_profile("Bob", 25, "NYC"))

# Output: {'name': 'Bob', 'age': 25, 'city': 'NYC', 'active': True}

print(create_profile("Charlie", city="LA"))

# Output: {'name': 'Charlie', 'age': 18, 'city': 'LA', 'active': True}

# GOTCHA: Mutable default arguments

def add_item_bad(item, items=[]):

"""Bad: Mutable default persists across calls!"""

items.append(item)

return items

print(add_item_bad("apple")) # Output: ['apple']

print(add_item_bad("banana")) # Output: ['apple', 'banana'] - Unexpected!

# CORRECT: Use None and create new mutable inside

def add_item_good(item, items=None):

"""Good: Create new list for each call."""

if items is None:

items = []

items.append(item)

return items

print(add_item_good("apple")) # Output: ['apple']

print(add_item_good("banana")) # Output: ['banana'] - Correct!

# Default arguments must follow non-default

# def invalid(a=1, b): # SyntaxError!

# pass

def valid(a, b=1, c=2):

"""Valid: defaults after required parameters."""

return a + b + c

print(valid(5)) # Output: 8 (5 + 1 + 2)

print(valid(5, 10)) # Output: 17 (5 + 10 + 2)

print(valid(5, 10, 20)) # Output: 35None as default and create new mutable objects inside the function.Variable-Length Arguments

Variable-length arguments enable functions to accept arbitrary numbers of positional or keyword arguments, providing flexibility for functions like sum, max, or print that work with varying input counts. The *args syntax collects extra positional arguments into a tuple, while **kwargs collects extra keyword arguments into a dictionary, enabling generic function signatures accommodating unpredictable argument patterns. These features are particularly useful for wrapper functions, decorator implementations, and APIs requiring flexible interfaces.

# Variable-Length Arguments: *args and **kwargs

# *args: Variable positional arguments

def sum_all(*args):

"""Sum any number of arguments."""

return sum(args)

print(sum_all(1, 2, 3)) # Output: 6

print(sum_all(10, 20, 30, 40)) # Output: 100

print(sum_all(5)) # Output: 5

# *args collects into tuple

def print_args(*args):

"""Print all positional arguments."""

print(f"Type: {type(args)}")

print(f"Args: {args}")

for i, arg in enumerate(args):

print(f" Arg {i}: {arg}")

print_args("apple", "banana", "cherry")

# Output:

# Type: <class 'tuple'>

# Args: ('apple', 'banana', 'cherry')

# Arg 0: apple

# Arg 1: banana

# Arg 2: cherry

# **kwargs: Variable keyword arguments

def print_info(**kwargs):

"""Print all keyword arguments."""

print(f"Type: {type(kwargs)}")

for key, value in kwargs.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")

print_info(name="Alice", age=25, city="NYC")

# Output:

# Type: <class 'dict'>

# name: Alice

# age: 25

# city: NYC

# Combining regular, *args, and **kwargs

def flexible_function(required, default="default", *args, **kwargs):

"""Function with all argument types."""

print(f"Required: {required}")

print(f"Default: {default}")

print(f"Args: {args}")

print(f"Kwargs: {kwargs}")

flexible_function(

"must_provide",

"custom_default",

"extra1", "extra2",

key1="value1",

key2="value2"

)

# Output:

# Required: must_provide

# Default: custom_default

# Args: ('extra1', 'extra2')

# Kwargs: {'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2'}

# Practical example: Custom print function

def custom_print(*args, sep=' ', end='\n'):

"""Custom print with default separator."""

output = sep.join(str(arg) for arg in args)

print(output, end=end)

custom_print("Hello", "World") # Output: Hello World

custom_print(1, 2, 3, sep='-') # Output: 1-2-3

custom_print("A", "B", "C", sep=', ', end='!\n') # Output: A, B, C!

# Wrapper function example

def logged_function(*args, **kwargs):

"""Wrapper that logs calls."""

print(f"Called with args: {args}, kwargs: {kwargs}")

# Forward to another function

return some_function(*args, **kwargs)

def some_function(a, b, c=0):

return a + b + c

result = logged_function(10, 20, c=5)

print(f"Result: {result}")Function Scope and Variables

Variable scope determines where variables can be accessed in code, with Python following the LEGB rule: Local (inside function), Enclosing (in outer functions), Global (module level), and Built-in (Python keywords). Variables created inside functions have local scope visible only within that function, while global variables exist at module level accessible everywhere but requiring the global keyword for modification inside functions. Understanding scope prevents bugs from unexpected variable shadowing, unintended global modifications, and namespace collisions.

# Function Scope and Variables

# Local scope

def my_function():

"""Local variable only accessible inside function."""

local_var = "I'm local"

print(local_var)

my_function() # Output: I'm local

# print(local_var) # NameError: local_var not defined

# Global scope

global_var = "I'm global"

def access_global():

"""Functions can read global variables."""

print(global_var)

access_global() # Output: I'm global

# Modifying global variables

counter = 0

def increment_wrong():

"""This creates a local variable instead!"""

counter = counter + 1 # UnboundLocalError!

def increment_correct():

"""Use global keyword to modify global variable."""

global counter

counter = counter + 1

increment_correct()

print(counter) # Output: 1

# Variable shadowing

name = "Global"

def shadowing_example():

"""Local variable shadows global variable."""

name = "Local" # Creates new local variable

print(f"Inside function: {name}")

shadowing_example() # Output: Inside function: Local

print(f"Outside function: {name}") # Output: Outside function: Global

# Enclosing scope (nested functions)

def outer():

"""Outer function with nested function."""

outer_var = "Outer"

def inner():

"""Inner function accesses outer variable."""

print(f"Inner sees: {outer_var}")

inner()

print(f"Outer sees: {outer_var}")

outer()

# Output:

# Inner sees: Outer

# Outer sees: Outer

# nonlocal keyword for enclosing scope

def counter_function():

"""Create counter with enclosed state."""

count = 0

def increment():

nonlocal count # Modify enclosing variable

count += 1

return count

return increment

my_counter = counter_function()

print(my_counter()) # Output: 1

print(my_counter()) # Output: 2

print(my_counter()) # Output: 3

# LEGB Rule example

built_in = len # Built-in function

global_var = "global" # Global scope

def outer_func():

enclosing_var = "enclosing" # Enclosing scope

def inner_func():

local_var = "local" # Local scope

# Can access all scopes

print(f"Local: {local_var}")

print(f"Enclosing: {enclosing_var}")

print(f"Global: {global_var}")

print(f"Built-in: {built_in([1, 2, 3])}")

inner_func()

outer_func()Lambda Functions

Lambda functions are anonymous single-expression functions created with the lambda keyword, useful for simple operations passed as arguments to higher-order functions like map(), filter(), and sorted(). While concise, lambda functions are limited to single expressions without statements or multiple lines, making them suitable only for simple operations where defining a full function would be verbose. For complex logic, use regular named functions with descriptive names improving code readability and maintainability.

# Lambda Functions

# Basic lambda syntax: lambda arguments: expression

square = lambda x: x ** 2

print(square(5)) # Output: 25

# Lambda with multiple arguments

add = lambda a, b: a + b

print(add(3, 7)) # Output: 10

# Lambda vs regular function

def multiply_func(x, y):

return x * y

multiply_lambda = lambda x, y: x * y

print(multiply_func(4, 5)) # Output: 20

print(multiply_lambda(4, 5)) # Output: 20

# Lambda with map()

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squared = list(map(lambda x: x ** 2, numbers))

print(squared) # Output: [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

# Lambda with filter()

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

evens = list(filter(lambda x: x % 2 == 0, numbers))

print(evens) # Output: [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

# Lambda with sorted()

students = [

{'name': 'Alice', 'grade': 85},

{'name': 'Bob', 'grade': 92},

{'name': 'Charlie', 'grade': 78}

]

# Sort by grade

sorted_students = sorted(students, key=lambda s: s['grade'], reverse=True)

for student in sorted_students:

print(f"{student['name']}: {student['grade']}")

# Output:

# Bob: 92

# Alice: 85

# Charlie: 78

# Lambda in list comprehension alternative

# Lambda: list(map(lambda x: x * 2, numbers))

# List comp: [x * 2 for x in numbers] # More Pythonic

# Lambda with conditional expression

absolute = lambda x: x if x >= 0 else -x

print(absolute(-5)) # Output: 5

print(absolute(10)) # Output: 10

# Practical: Custom sorting

words = ['Python', 'is', 'amazing', 'and', 'powerful']

# Sort by length

by_length = sorted(words, key=lambda w: len(w))

print(by_length) # Output: ['is', 'and', 'Python', 'amazing', 'powerful']

# Sort by last letter

by_last = sorted(words, key=lambda w: w[-1])

print(by_last) # Output: ['amazing', 'and', 'powerful', 'Python', 'is']

# When NOT to use lambda

# Bad: Complex logic in lambda

# complicated = lambda x: x ** 2 if x > 0 else -x ** 2 if x < 0 else 0

# Good: Use regular function

def process_number(x):

"""Process number with complex logic."""

if x > 0:

return x ** 2

elif x < 0:

return -x ** 2

else:

return 0Function Best Practices

- Single responsibility: Each function should do one thing well. If a function does multiple tasks, split it into separate functions for better modularity and testing

- Descriptive names: Use clear, verb-based names describing what the function does:

calculate_total(),fetch_user_data(),validate_email() - Document with docstrings: Add docstrings explaining purpose, parameters, return values, and exceptions for all public functions following PEP 257 conventions

- Limit parameters: Functions with many parameters are hard to use. Aim for 3-4 parameters maximum; use objects or dictionaries for complex parameter sets

- Avoid side effects: Functions should avoid modifying global state or arguments. Pure functions returning new values are easier to test and reason about

- Use type hints: Add type annotations for parameters and return values in Python 3.5+ to improve IDE support and enable static type checking

- Return early: Use early returns to handle edge cases and errors at the start of functions, reducing nesting and improving readability

- Avoid mutable defaults: Never use lists or dictionaries as default arguments. Use

Noneand create new objects inside the function - Keep functions short: Functions longer than 20-30 lines should often be split. Short functions are easier to understand, test, and maintain

- Consistent abstraction level: All statements in a function should operate at the same level of abstraction, delegating details to helper functions

Conclusion

Python functions are fundamental building blocks enabling code reusability, modularity, and organization by encapsulating logic that can be called multiple times with different inputs, reducing duplication and improving maintainability. Function definition uses the def keyword followed by descriptive names, parameters in parentheses, colons, and indented code blocks containing function bodies with optional return statements sending values back to callers or implicitly returning None if no return is specified. Parameters and arguments distinguish between variables defined in function signatures and actual values passed during calls, with positional arguments matching by order, keyword arguments matching by name enabling flexible calling, and combinations requiring positional arguments before keyword arguments to avoid syntax errors.

Default arguments provide fallback values making parameters optional through = assignment in function signatures, but require awareness of mutable default gotcha where lists and dictionaries persist across calls, necessitating the idiom of using None as default and creating new mutable objects inside functions. Variable-length arguments enable flexible interfaces through *args collecting extra positional arguments into tuples and **kwargs collecting extra keyword arguments into dictionaries, particularly useful for wrapper functions, decorators, and APIs requiring unpredictable argument patterns. Function scope follows the LEGB rule searching Local, Enclosing, Global, and Built-in namespaces, with local variables visible only within functions, global variables accessible everywhere but requiring global keyword for modification, and nonlocal keyword enabling modification of enclosing function variables. Lambda functions provide anonymous single-expression functions using lambda keyword suitable for simple operations passed to higher-order functions like map(), filter(), and sorted(), though regular named functions should be preferred for complex logic improving readability. Best practices emphasize single responsibility with functions doing one thing well, descriptive verb-based names, comprehensive docstrings following PEP 257, limiting parameters to 3-4 maximum, avoiding side effects for testability, using type hints for tooling support, returning early to reduce nesting, avoiding mutable default arguments, keeping functions short under 30 lines, and maintaining consistent abstraction levels. By mastering function definition, parameters and arguments, default values, variable-length arguments, scope rules, lambda expressions, and best practices, you gain essential skills for writing organized, maintainable, and professional Python code following software engineering principles that enable building complex applications through composition of simple, well-designed, reusable functions.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!