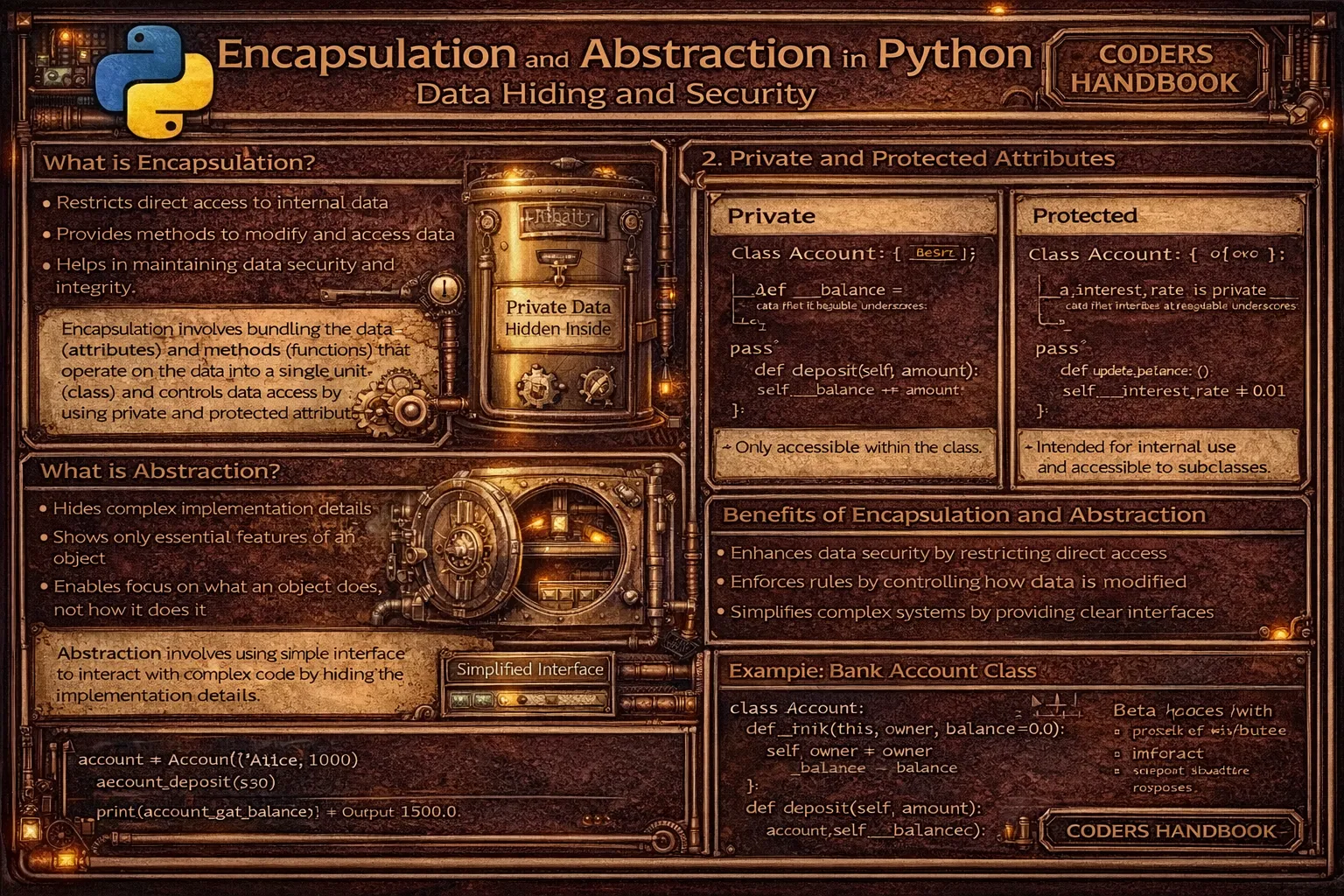

Encapsulation and Abstraction in Python: Data Hiding and Security

Encapsulation and abstraction are fundamental object-oriented programming principles controlling access to object internals and defining clear interfaces. Encapsulation bundles data and methods operating on that data within classes while restricting direct access to internal state, protecting objects from invalid modifications and maintaining invariants. Python implements encapsulation through naming conventions using single underscore for protected members intended for internal use, double underscore for private members triggering name mangling making them harder to access externally, property decorators providing controlled attribute access through getters and setters, and accessor methods encapsulating validation logic. Abstraction hides implementation complexity exposing only essential features through well-defined interfaces, with abstract base classes using the abc module defining method signatures that concrete subclasses must implement.

This comprehensive guide explores public attributes and methods accessible from anywhere without restrictions, protected members using single underscore prefix _attribute indicating internal use discouraged but not prevented, private members with double underscore prefix __attribute triggering name mangling to _ClassName__attribute making external access intentionally difficult, property decorators using @property for getters returning computed or validated values, @attribute.setter for setters validating assignments before updating state, and @attribute.deleter for cleanup operations, practical encapsulation patterns validating input ranges, computed properties deriving values from other attributes, and read-only properties preventing modifications, abstract base classes with abc.ABC base class and @abstractmethod decorator forcing subclass implementation, creating interfaces defining method contracts without implementations, type hints with protocols defining structural interfaces through duck typing, and best practices using encapsulation for validation and consistency, preferring properties over direct getters and setters, keeping internal state private, documenting public interfaces clearly, and using abstraction to reduce coupling. Whether you're building robust classes protecting internal state, creating flexible APIs with controlled access, implementing validation preventing invalid data, designing frameworks with abstract interfaces, or organizing complex systems hiding implementation details, mastering encapsulation and abstraction provides essential tools for secure, maintainable code with clear boundaries supporting extensible Python applications.

Access Modifiers: Public, Protected, Private

Python uses naming conventions to indicate intended access levels rather than enforced access control like Java or C++. Public members have no prefix and are accessible from anywhere, protected members use single underscore prefix indicating internal use, and private members use double underscore prefix triggering name mangling. Understanding these conventions enables proper encapsulation communicating intended usage while respecting Python's philosophy that we're all consenting adults.

# Access Modifiers: Public, Protected, Private

# === Public members (no prefix) ===

class BankAccount:

"""Bank account with different access levels."""

def __init__(self, account_number, balance):

# Public attributes - accessible anywhere

self.account_number = account_number

self.balance = balance

# Public method - accessible anywhere

def deposit(self, amount):

if amount > 0:

self.balance += amount

return True

return False

account = BankAccount("123456", 1000)

print(account.account_number) # 123456 - direct access OK

print(account.balance) # 1000 - direct access OK

account.deposit(500) # Public method call

# === Protected members (single underscore) ===

class Employee:

"""Employee with protected members."""

def __init__(self, name, salary):

self.name = name # Public

self._salary = salary # Protected (convention)

self._department = "General" # Protected

def _calculate_bonus(self): # Protected method

"""Internal calculation method."""

return self._salary * 0.1

def get_total_compensation(self):

"""Public method using protected members."""

return self._salary + self._calculate_bonus()

emp = Employee("Alice", 50000)

# Can access protected members (but shouldn't)

print(emp._salary) # 50000 - accessible but discouraged

print(emp._calculate_bonus()) # 5000.0 - accessible but discouraged

# Should use public interface

print(emp.get_total_compensation()) # 55000.0 - proper way

# Protected members in inheritance

class Manager(Employee):

def __init__(self, name, salary):

super().__init__(name, salary)

self._department = "Management" # Can access protected

def get_bonus(self):

# Subclass can access protected members

return self._calculate_bonus()

manager = Manager("Bob", 80000)

print(manager.get_bonus()) # 8000.0

# === Private members (double underscore) ===

class SecureBankAccount:

"""Bank account with private members."""

def __init__(self, account_number, pin):

self.account_number = account_number # Public

self.__pin = pin # Private

self.__balance = 0 # Private

def __validate_pin(self, pin): # Private method

"""Validate PIN (private method)."""

return pin == self.__pin

def withdraw(self, amount, pin):

"""Public method with PIN validation."""

if not self.__validate_pin(pin):

return "Invalid PIN"

if amount > self.__balance:

return "Insufficient funds"

self.__balance -= amount

return f"Withdrew ${amount}"

def deposit(self, amount, pin):

if not self.__validate_pin(pin):

return "Invalid PIN"

self.__balance += amount

return f"Deposited ${amount}"

def get_balance(self, pin):

if not self.__validate_pin(pin):

return "Invalid PIN"

return self.__balance

account = SecureBankAccount("789012", "1234")

# Cannot access private members directly

# print(account.__pin) # AttributeError

# print(account.__balance) # AttributeError

# Must use public interface

account.deposit(1000, "1234")

print(account.get_balance("1234")) # 1000

print(account.get_balance("0000")) # Invalid PIN

# === Name mangling for private members ===

class Example:

def __init__(self):

self.__private = "Private value"

self._protected = "Protected value"

self.public = "Public value"

obj = Example()

# Accessing public and protected (OK)

print(obj.public) # Public value

print(obj._protected) # Protected value

# Accessing private (mangled name)

# print(obj.__private) # AttributeError

print(obj._Example__private) # Private value (name mangling)

# Name mangling mechanism

print(dir(obj))

# Shows: _Example__private (mangled), _protected, public

# === Practical example: Person class ===

class Person:

"""Person with proper encapsulation."""

def __init__(self, name, age, ssn):

self.name = name # Public

self._age = age # Protected (internal use)

self.__ssn = ssn # Private (sensitive data)

def get_age(self):

"""Public getter for age."""

return self._age

def set_age(self, age):

"""Public setter with validation."""

if 0 <= age <= 150:

self._age = age

return True

return False

def __mask_ssn(self):

"""Private method to mask SSN."""

return f"***-**-{self.__ssn[-4:]}"

def display_info(self):

"""Public method using private method."""

return f"{self.name}, Age: {self._age}, SSN: {self.__mask_ssn()}"

person = Person("John Doe", 30, "123-45-6789")

# Public access

print(person.name) # John Doe

# Protected access (discouraged)

print(person._age) # 30

# Private access (intentionally difficult)

# print(person.__ssn) # AttributeError

# print(person.__mask_ssn()) # AttributeError

# Proper way to access

print(person.get_age()) # 30

print(person.display_info()) # John Doe, Age: 30, SSN: ***-**-6789

# === Why Python doesn't enforce privacy ===

# Python philosophy: "We're all consenting adults"

# - Conventions signal intent, not strict enforcement

# - Developers responsible for respecting conventions

# - Name mangling provides barrier, not security

# - Allows debugging and testing flexibilityProperty Decorators: Getters and Setters

Property decorators provide Pythonic getters and setters enabling attribute-like access while executing validation logic and computed values. The @property decorator defines getters making methods accessible like attributes, @attribute.setter defines setters validating values before assignment, and @attribute.deleter handles cleanup. Properties enable changing implementation from simple attributes to computed or validated values without modifying calling code.

# Property Decorators: Getters and Setters

# === Basic property usage ===

class Temperature:

"""Temperature with Celsius and Fahrenheit properties."""

def __init__(self, celsius=0):

self._celsius = celsius

@property

def celsius(self):

"""Getter for celsius."""

print("Getting celsius")

return self._celsius

@celsius.setter

def celsius(self, value):

"""Setter for celsius with validation."""

print(f"Setting celsius to {value}")

if value < -273.15:

raise ValueError("Temperature below absolute zero!")

self._celsius = value

@property

def fahrenheit(self):

"""Computed property: Celsius to Fahrenheit."""

return self._celsius * 9/5 + 32

@fahrenheit.setter

def fahrenheit(self, value):

"""Set temperature via Fahrenheit."""

self._celsius = (value - 32) * 5/9

temp = Temperature(25)

# Property access (looks like attribute)

print(temp.celsius) # 25 (calls getter)

temp.celsius = 30 # Calls setter with validation

print(temp.celsius) # 30

# Computed property

print(temp.fahrenheit) # 86.0 (computed from celsius)

temp.fahrenheit = 100 # Sets celsius via fahrenheit

print(temp.celsius) # 37.77...

# Validation in action

try:

temp.celsius = -300 # Below absolute zero

except ValueError as e:

print(e) # Temperature below absolute zero!

# === Read-only property ===

class Circle:

"""Circle with read-only diameter."""

def __init__(self, radius):

self._radius = radius

@property

def radius(self):

return self._radius

@radius.setter

def radius(self, value):

if value < 0:

raise ValueError("Radius cannot be negative")

self._radius = value

@property

def diameter(self):

"""Read-only computed property."""

return self._radius * 2

@property

def area(self):

"""Read-only computed property."""

return 3.14159 * self._radius ** 2

circle = Circle(5)

print(circle.radius) # 5

print(circle.diameter) # 10 (computed)

print(circle.area) # 78.53975 (computed)

circle.radius = 10 # Can modify radius

print(circle.diameter) # 20 (automatically updated)

# Cannot set diameter (no setter)

try:

circle.diameter = 30

except AttributeError as e:

print("Cannot set diameter") # Read-only property

# === Property with deleter ===

class Account:

"""Account with property deleter."""

def __init__(self, balance=0):

self._balance = balance

@property

def balance(self):

return self._balance

@balance.setter

def balance(self, value):

if value < 0:

raise ValueError("Balance cannot be negative")

self._balance = value

@balance.deleter

def balance(self):

"""Clear balance when deleted."""

print("Deleting balance attribute")

self._balance = 0

account = Account(1000)

print(account.balance) # 1000

del account.balance # Calls deleter

print(account.balance) # 0

# === Properties vs traditional getters/setters ===

# Traditional approach (not Pythonic)

class OldStyle:

def __init__(self, value):

self._value = value

def get_value(self):

return self._value

def set_value(self, value):

if value < 0:

raise ValueError("Value must be positive")

self._value = value

# Usage (verbose)

obj = OldStyle(10)

print(obj.get_value()) # Need method call

obj.set_value(20) # Need method call

# Pythonic approach (with properties)

class NewStyle:

def __init__(self, value):

self._value = value

@property

def value(self):

return self._value

@value.setter

def value(self, value):

if value < 0:

raise ValueError("Value must be positive")

self._value = value

# Usage (clean and intuitive)

obj = NewStyle(10)

print(obj.value) # Attribute-like access

obj.value = 20 # Attribute-like assignment

# === Validation with properties ===

class Person:

"""Person with validated properties."""

def __init__(self, name, age):

self._name = name

self._age = age

@property

def name(self):

return self._name

@name.setter

def name(self, value):

if not isinstance(value, str):

raise TypeError("Name must be a string")

if len(value) < 2:

raise ValueError("Name must be at least 2 characters")

self._name = value

@property

def age(self):

return self._age

@age.setter

def age(self, value):

if not isinstance(value, int):

raise TypeError("Age must be an integer")

if value < 0 or value > 150:

raise ValueError("Age must be between 0 and 150")

self._age = value

person = Person("Alice", 30)

# Valid assignments

person.name = "Bob"

person.age = 25

# Invalid assignments

try:

person.name = "A" # Too short

except ValueError as e:

print(e)

try:

person.age = 200 # Out of range

except ValueError as e:

print(e)

# === Caching with properties ===

class DataProcessor:

"""Data processor with cached property."""

def __init__(self, data):

self._data = data

self._processed_data = None

@property

def data(self):

return self._data

@data.setter

def data(self, value):

self._data = value

self._processed_data = None # Invalidate cache

@property

def processed_data(self):

"""Lazy evaluation with caching."""

if self._processed_data is None:

print("Processing data...")

# Expensive operation

self._processed_data = [x * 2 for x in self._data]

return self._processed_data

processor = DataProcessor([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

# First access: processes data

print(processor.processed_data) # Processing data... [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

# Second access: uses cache

print(processor.processed_data) # [2, 4, 6, 8, 10] (no processing message)

# Changing data invalidates cache

processor.data = [10, 20, 30]

print(processor.processed_data) # Processing data... [20, 40, 60]Abstract Base Classes

Abstract base classes (ABCs) using the abc module define interfaces specifying methods that concrete subclasses must implement, enforcing contracts without providing implementations. Classes inheriting from abc.ABC and marking methods with @abstractmethod decorator cannot be instantiated until all abstract methods are implemented. ABCs enable polymorphism through well-defined interfaces, ensuring subclasses provide required functionality while hiding implementation details.

# Abstract Base Classes

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

# === Basic abstract class ===

class Shape(ABC):

"""Abstract base class for shapes."""

@abstractmethod

def area(self):

"""Calculate area (must be implemented by subclasses)."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def perimeter(self):

"""Calculate perimeter (must be implemented by subclasses)."""

pass

def describe(self):

"""Concrete method (has implementation)."""

return f"This shape has area {self.area()} and perimeter {self.perimeter()}"

# Cannot instantiate abstract class

try:

shape = Shape()

except TypeError as e:

print(e) # Can't instantiate abstract class Shape

# Concrete implementation

class Rectangle(Shape):

"""Concrete rectangle class."""

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def area(self):

"""Implement required abstract method."""

return self.width * self.height

def perimeter(self):

"""Implement required abstract method."""

return 2 * (self.width + self.height)

class Circle(Shape):

"""Concrete circle class."""

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def area(self):

return 3.14159 * self.radius ** 2

def perimeter(self):

return 2 * 3.14159 * self.radius

# Can instantiate concrete classes

rect = Rectangle(10, 5)

print(rect.area()) # 50

print(rect.describe()) # This shape has area 50 and perimeter 30

circle = Circle(7)

print(circle.area()) # 153.93791

print(circle.describe()) # This shape has area 153.93791 and perimeter 43.98226

# === Incomplete implementation fails ===

class IncompleteShape(Shape):

"""Missing perimeter implementation."""

def area(self):

return 0

# Missing perimeter() implementation!

# Cannot instantiate - missing abstract method

try:

incomplete = IncompleteShape()

except TypeError as e:

print(e) # Can't instantiate abstract class IncompleteShape

# === Abstract class for database connection ===

class DatabaseConnection(ABC):

"""Abstract interface for database connections."""

@abstractmethod

def connect(self):

"""Establish connection."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def disconnect(self):

"""Close connection."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def execute(self, query):

"""Execute query."""

pass

def log(self, message):

"""Concrete logging method."""

print(f"[DB] {message}")

class MySQLConnection(DatabaseConnection):

"""MySQL implementation."""

def connect(self):

self.log("Connecting to MySQL")

return "MySQL connected"

def disconnect(self):

self.log("Disconnecting from MySQL")

return "MySQL disconnected"

def execute(self, query):

self.log(f"Executing MySQL query: {query}")

return f"MySQL result for: {query}"

class PostgreSQLConnection(DatabaseConnection):

"""PostgreSQL implementation."""

def connect(self):

self.log("Connecting to PostgreSQL")

return "PostgreSQL connected"

def disconnect(self):

self.log("Disconnecting from PostgreSQL")

return "PostgreSQL disconnected"

def execute(self, query):

self.log(f"Executing PostgreSQL query: {query}")

return f"PostgreSQL result for: {query}"

# Polymorphic usage

def run_query(connection: DatabaseConnection, query):

"""Works with any DatabaseConnection implementation."""

connection.connect()

result = connection.execute(query)

connection.disconnect()

return result

mysql = MySQLConnection()

postgres = PostgreSQLConnection()

run_query(mysql, "SELECT * FROM users")

run_query(postgres, "SELECT * FROM users")

# === Abstract properties ===

class Animal(ABC):

"""Abstract animal with abstract properties."""

@property

@abstractmethod

def species(self):

"""Abstract property - must be overridden."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def make_sound(self):

"""Abstract method."""

pass

class Dog(Animal):

"""Concrete dog implementation."""

@property

def species(self):

return "Canis familiaris"

def make_sound(self):

return "Woof!"

dog = Dog()

print(dog.species) # Canis familiaris

print(dog.make_sound()) # Woof!

# === Abstract class with __init__ ===

class Vehicle(ABC):

"""Abstract vehicle with initialization."""

def __init__(self, brand, model):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

@abstractmethod

def start(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def stop(self):

pass

def info(self):

return f"{self.brand} {self.model}"

class Car(Vehicle):

def start(self):

return f"{self.info()} starting with ignition"

def stop(self):

return f"{self.info()} stopping with brakes"

class ElectricCar(Vehicle):

def start(self):

return f"{self.info()} starting silently"

def stop(self):

return f"{self.info()} stopping with regenerative brakes"

car = Car("Toyota", "Camry")

ev = ElectricCar("Tesla", "Model 3")

print(car.start()) # Toyota Camry starting with ignition

print(ev.start()) # Tesla Model 3 starting silently

# === Multiple abstract methods ===

class PaymentProcessor(ABC):

"""Abstract payment processor."""

@abstractmethod

def validate(self, payment_info):

"""Validate payment information."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def process(self, amount):

"""Process payment."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def refund(self, transaction_id):

"""Refund transaction."""

pass

class CreditCardProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def validate(self, payment_info):

return f"Validating credit card: {payment_info}"

def process(self, amount):

return f"Processing ${amount} via credit card"

def refund(self, transaction_id):

return f"Refunding transaction {transaction_id}"

# Must implement all abstract methods

processor = CreditCardProcessor()

print(processor.validate("1234-5678-9012-3456"))

print(processor.process(100.00))

print(processor.refund("TXN123"))@abstractmethod to define required methods. Subclasses cannot be instantiated until all abstract methods are implemented.Encapsulation and Abstraction Best Practices

- Prefer properties over getters/setters: Use

@propertyfor Pythonic attribute access instead ofget_value()andset_value()methods - Validate in setters: Use property setters to validate input preventing invalid state. Raise

ValueErrororTypeErrorfor invalid values - Use single underscore for internal members: Prefix internal methods and attributes with

_signaling they're implementation details not part of public API - Use double underscore for truly private data: Use

__prefix only for attributes requiring name mangling to avoid conflicts in inheritance - Document public interfaces: Clearly document which attributes and methods are public API. Use docstrings explaining expected usage and behavior

- Keep implementation details private: Hide internal state and helper methods. Expose only essential interfaces enabling implementation changes without breaking code

- Use ABCs for interface design: Define abstract base classes establishing contracts for related classes. Use

@abstractmethodenforcing implementation - Provide read-only properties when appropriate: Use

@propertywithout@setterfor computed values or attributes that shouldn't be modified externally - Don't over-encapsulate: Python philosophy trusts developers. Don't make everything private. Use conventions appropriately without excessive protection

- Maintain invariants through encapsulation: Use private attributes and validation ensuring object state remains consistent. Don't allow invalid states

Conclusion

Encapsulation and abstraction control access to object internals and define clear interfaces enabling secure, maintainable code with well-defined boundaries. Python implements encapsulation through naming conventions with public members accessible anywhere without restrictions, protected members using single underscore prefix _attribute indicating internal use discouraged but not prevented, and private members with double underscore prefix __attribute triggering name mangling to _ClassName__attribute making external access intentionally difficult though not impossible. Property decorators provide Pythonic attribute access with validation using @property for getters returning values or computing derived properties, @attribute.setter for setters validating assignments before updating state preventing invalid data, and @attribute.deleter for cleanup operations, enabling changing implementations from simple attributes to validated or computed values without modifying calling code maintaining backward compatibility.

Abstract base classes using abc.ABC and @abstractmethod decorator define interfaces specifying methods concrete subclasses must implement enforcing contracts without providing implementations, preventing instantiation until all abstract methods are implemented ensuring complete implementation. ABCs enable polymorphism through well-defined interfaces with classes implementing required methods working interchangeably, abstract properties using @property with @abstractmethod requiring property implementations in subclasses, and abstract classes with __init__ providing common initialization while requiring abstract method implementation. Best practices emphasize preferring properties over traditional getters and setters for Pythonic attribute-like access, validating in setters preventing invalid state by raising appropriate exceptions, using single underscore for internal members signaling implementation details, using double underscore only for truly private data requiring name mangling, documenting public interfaces clearly with docstrings, keeping implementation details private enabling changes without breaking external code, using ABCs for interface design establishing contracts, providing read-only properties for computed or immutable values, avoiding over-encapsulation respecting Python's consenting adults philosophy, and maintaining invariants through encapsulation ensuring consistent object state. By mastering access modifiers communicating intended usage, property decorators providing controlled attribute access with validation, abstract base classes defining enforceable interfaces, encapsulation patterns protecting internal state, and best practices balancing protection with pragmatism, you gain essential tools for building secure robust classes with clear boundaries, flexible APIs supporting evolution, validated data preventing corruption, abstract interfaces enabling polymorphism, and maintainable code hiding complexity supporting professional Python development from business applications to framework design.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!