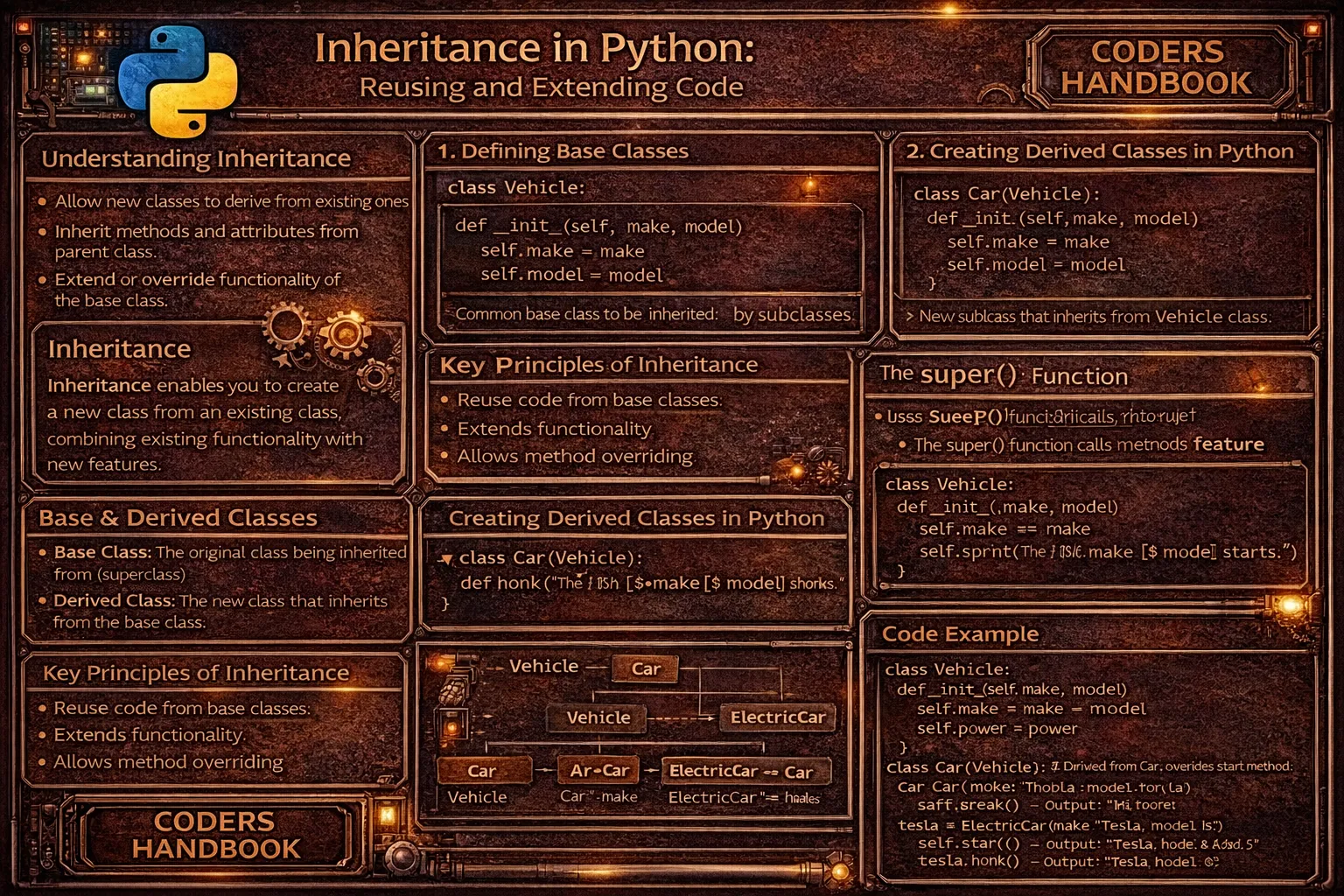

Inheritance in Python: Reusing and Extending Code

Inheritance is a fundamental object-oriented programming mechanism enabling new classes to derive from existing classes, inheriting attributes and methods while adding or modifying functionality. Child classes (subclasses or derived classes) inherit from parent classes (superclasses or base classes), gaining access to parent attributes and methods without reimplementing them, promoting code reuse and establishing hierarchical relationships modeling real-world is-a relationships like Dog is-a Animal or SavingsAccount is-a BankAccount. This mechanism enables building specialized classes extending general ones, overriding inherited methods to customize behavior, calling parent methods using super() to extend rather than replace functionality, and creating class hierarchies organizing related objects sharing common interfaces and behaviors.

This comprehensive guide explores single inheritance creating child classes from single parents establishing straightforward hierarchies, defining child classes with class ChildClass(ParentClass) syntax, inheriting attributes and methods automatically available in child instances, method overriding replacing parent implementations with specialized versions, using super() to call parent class methods accessing overridden functionality, the __init__ constructor inheritance requiring explicit super().__init__() calls to initialize parent state, adding new attributes and methods extending parent functionality, multiple inheritance inheriting from multiple parent classes combining behaviors, Method Resolution Order (MRO) determining which parent method executes when names conflict using C3 linearization algorithm, the diamond problem occurring when multiple inheritance paths lead to common ancestor, practical inheritance hierarchies modeling employees, vehicles, or shapes, and best practices preferring composition over inheritance for has-a relationships, keeping hierarchies shallow avoiding deep nesting, using abstract base classes defining interfaces, and documenting inheritance relationships clearly. Whether you're building class hierarchies for domain models, creating specialized exceptions extending base exception classes, implementing frameworks with extensible base classes, modeling business entities with shared attributes, or organizing related functionality through inheritance trees, mastering inheritance provides essential tools for code reuse, polymorphism, and hierarchical organization supporting maintainable, extensible Python applications.

Single Inheritance Basics

Single inheritance creates child classes inheriting from one parent class using the syntax class Child(Parent), automatically gaining access to parent attributes and methods. Child instances can use inherited methods directly, extend functionality by adding new methods, and access parent attributes without redefining them. Understanding basic inheritance establishes foundations for code reuse patterns avoiding duplication while maintaining clear hierarchical relationships.

# Single Inheritance Basics

# === Simple inheritance example ===

class Animal:

"""Base class representing an animal."""

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def speak(self):

return f"{self.name} makes a sound"

def move(self):

return f"{self.name} is moving"

# Child class inherits from Animal

class Dog(Animal):

"""Dog class inheriting from Animal."""

def __init__(self, name, age, breed):

# Call parent constructor

super().__init__(name, age)

# Add new attribute

self.breed = breed

def bark(self):

"""Method specific to Dog."""

return f"{self.name} says Woof!"

# Create Dog instance

dog = Dog("Buddy", 3, "Golden Retriever")

# Use inherited methods

print(dog.speak()) # Buddy makes a sound

print(dog.move()) # Buddy is moving

# Use Dog-specific method

print(dog.bark()) # Buddy says Woof!

# Access inherited and new attributes

print(dog.name) # Buddy (inherited)

print(dog.breed) # Golden Retriever (new)

# === Checking inheritance relationships ===

print(isinstance(dog, Dog)) # True

print(isinstance(dog, Animal)) # True (Dog is-a Animal)

print(isinstance(dog, str)) # False

# Check if class is subclass

print(issubclass(Dog, Animal)) # True

print(issubclass(Animal, Dog)) # False

# === Inheritance hierarchy ===

class Vehicle:

"""Base vehicle class."""

def __init__(self, brand, model, year):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.odometer = 0

def start(self):

return f"{self.brand} {self.model} is starting"

def drive(self, miles):

self.odometer += miles

return f"Driven {miles} miles. Total: {self.odometer}"

class Car(Vehicle):

"""Car inherits from Vehicle."""

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, doors):

super().__init__(brand, model, year)

self.doors = doors

def honk(self):

return "Beep beep!"

class ElectricCar(Car):

"""ElectricCar inherits from Car."""

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, doors, battery_capacity):

super().__init__(brand, model, year, doors)

self.battery_capacity = battery_capacity

def charge(self):

return f"Charging {self.battery_capacity}kWh battery"

# Three-level inheritance

tesla = ElectricCar("Tesla", "Model 3", 2024, 4, 75)

print(tesla.start()) # Inherited from Vehicle

print(tesla.honk()) # Inherited from Car

print(tesla.charge()) # Specific to ElectricCar

print(tesla.drive(50)) # Inherited from Vehicle

# Check inheritance chain

print(isinstance(tesla, ElectricCar)) # True

print(isinstance(tesla, Car)) # True

print(isinstance(tesla, Vehicle)) # True

# === Inheriting class variables ===

class BankAccount:

"""Base bank account."""

# Class variable

interest_rate = 0.01

def __init__(self, account_number, balance=0):

self.account_number = account_number

self.balance = balance

def calculate_interest(self):

return self.balance * self.interest_rate

class SavingsAccount(BankAccount):

"""Savings account with higher interest."""

# Override class variable

interest_rate = 0.03

def __init__(self, account_number, balance=0, min_balance=100):

super().__init__(account_number, balance)

self.min_balance = min_balance

savings = SavingsAccount("S123", 1000)

print(savings.calculate_interest()) # 30.0 (uses 3% rate)

regular = BankAccount("R123", 1000)

print(regular.calculate_interest()) # 10.0 (uses 1% rate)class Child(Parent): to create inheritance. Child classes automatically inherit all parent attributes and methods without redefining them.Method Overriding

Method overriding replaces inherited method implementations with specialized versions in child classes, enabling polymorphism where different classes respond to the same method call with class-specific behavior. Child classes define methods with identical names as parent methods, and Python calls the child's version when invoked on child instances. This mechanism enables creating specialized behaviors while maintaining consistent interfaces across related classes.

# Method Overriding

# === Basic method overriding ===

class Animal:

"""Base animal class."""

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def speak(self):

return f"{self.name} makes a generic sound"

def info(self):

return f"This is {self.name}"

class Dog(Animal):

"""Dog overrides speak method."""

def speak(self):

# Completely replace parent implementation

return f"{self.name} says Woof!"

class Cat(Animal):

"""Cat overrides speak method."""

def speak(self):

return f"{self.name} says Meow!"

# Same method name, different behavior (polymorphism)

dog = Dog("Buddy")

cat = Cat("Whiskers")

print(dog.speak()) # Buddy says Woof! (overridden)

print(cat.speak()) # Whiskers says Meow! (overridden)

print(dog.info()) # This is Buddy (inherited, not overridden)

# Polymorphism example

animals = [Dog("Max"), Cat("Luna"), Dog("Charlie"), Cat("Oliver")]

for animal in animals:

print(animal.speak())

# Output:

# Max says Woof!

# Luna says Meow!

# Charlie says Woof!

# Oliver says Meow!

# === Overriding __init__ ===

class Person:

"""Base person class."""

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

print(f"Person.__init__ called for {name}")

def introduce(self):

return f"I'm {self.name}, {self.age} years old"

class Employee(Person):

"""Employee with additional attributes."""

def __init__(self, name, age, employee_id, salary):

# Must call parent __init__ to initialize inherited attributes

super().__init__(name, age)

# Initialize new attributes

self.employee_id = employee_id

self.salary = salary

print(f"Employee.__init__ called for {employee_id}")

def introduce(self):

# Override to include employee details

return f"I'm {self.name}, employee #{self.employee_id}"

emp = Employee("Alice", 30, "E001", 50000)

# Output:

# Person.__init__ called for Alice

# Employee.__init__ called for E001

print(emp.introduce()) # I'm Alice, employee #E001

# === Extending vs completely replacing ===

class Rectangle:

"""Rectangle base class."""

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def area(self):

return self.width * self.height

def describe(self):

return f"Rectangle: {self.width}x{self.height}, Area: {self.area()}"

class Square(Rectangle):

"""Square extending Rectangle."""

def __init__(self, side):

# Initialize as rectangle with equal sides

super().__init__(side, side)

def describe(self):

# Completely replace parent implementation

return f"Square: {self.width}x{self.width}, Area: {self.area()}"

square = Square(5)

print(square.area()) # 25 (inherited, not overridden)

print(square.describe()) # Square: 5x5, Area: 25 (overridden)

# === Calling parent method from override ===

class Logger:

"""Base logger."""

def log(self, message):

print(f"[LOG] {message}")

class TimestampLogger(Logger):

"""Logger with timestamps."""

def log(self, message):

from datetime import datetime

# Add timestamp then call parent method

timestamped = f"[{datetime.now().strftime('%H:%M:%S')}] {message}"

super().log(timestamped)

logger = TimestampLogger()

logger.log("Application started")

# Output: [LOG] [14:30:45] Application started

# === Override with validation ===

class BankAccount:

"""Basic bank account."""

def __init__(self, balance=0):

self.balance = balance

def withdraw(self, amount):

if amount > self.balance:

return "Insufficient funds"

self.balance -= amount

return f"Withdrew ${amount}. Balance: ${self.balance}"

class SavingsAccount(BankAccount):

"""Savings account with withdrawal limit."""

def __init__(self, balance=0, withdrawal_limit=1000):

super().__init__(balance)

self.withdrawal_limit = withdrawal_limit

def withdraw(self, amount):

# Additional validation before calling parent

if amount > self.withdrawal_limit:

return f"Exceeds withdrawal limit of ${self.withdrawal_limit}"

# Call parent withdraw method

return super().withdraw(amount)

account = SavingsAccount(5000, 1000)

print(account.withdraw(500)) # Withdrew $500. Balance: $4500

print(account.withdraw(1500)) # Exceeds withdrawal limit of $1000

print(account.withdraw(800)) # Withdrew $800. Balance: $3700__init__, always call super().__init__() to ensure parent class initialization runs. Forgetting this causes incomplete object initialization.The super() Function

The super() function provides access to parent class methods enabling child classes to extend rather than completely replace inherited functionality. Using super() in __init__ initializes parent attributes before adding child-specific ones, in overridden methods calls parent implementations adding behavior, and supports multiple inheritance through Method Resolution Order (MRO). Understanding super() enables proper parent method invocation avoiding direct parent class name references that break under inheritance changes.

# The super() Function

# === Basic super() usage ===

class Parent:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

print(f"Parent.__init__ with {value}")

def method(self):

return "Parent method"

class Child(Parent):

def __init__(self, value, child_value):

# Call parent's __init__

super().__init__(value)

self.child_value = child_value

print(f"Child.__init__ with {child_value}")

def method(self):

# Call parent's method and extend

parent_result = super().method()

return f"{parent_result} + Child method"

child = Child(10, 20)

# Output:

# Parent.__init__ with 10

# Child.__init__ with 20

print(child.method()) # Parent method + Child method

# === super() vs direct parent call ===

class Animal:

def speak(self):

return "Animal speaks"

class Dog(Animal):

def speak(self):

# Direct parent call (not recommended)

# result = Animal.speak(self)

# Using super() (recommended)

result = super().speak()

return f"{result} - Woof!"

dog = Dog()

print(dog.speak()) # Animal speaks - Woof!

# Why super() is better:

# 1. Works with multiple inheritance

# 2. Respects MRO (Method Resolution Order)

# 3. More flexible if inheritance changes

# === super() with arguments ===

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

class Student(Person):

def __init__(self, name, age, student_id, grade):

# Pass arguments to parent __init__

super().__init__(name, age)

self.student_id = student_id

self.grade = grade

class GraduateStudent(Student):

def __init__(self, name, age, student_id, grade, thesis_topic):

# Pass arguments through chain

super().__init__(name, age, student_id, grade)

self.thesis_topic = thesis_topic

grad = GraduateStudent("Alice", 25, "G001", "A", "AI Research")

print(grad.name) # Alice (from Person)

print(grad.student_id) # G001 (from Student)

print(grad.thesis_topic) # AI Research (from GraduateStudent)

# === super() for method chaining ===

class Base:

def process(self):

print("Base processing")

class MiddleA(Base):

def process(self):

print("MiddleA processing")

super().process()

class MiddleB(Base):

def process(self):

print("MiddleB processing")

super().process()

class Final(MiddleA, MiddleB):

def process(self):

print("Final processing")

super().process()

obj = Final()

obj.process()

# Output:

# Final processing

# MiddleA processing

# MiddleB processing

# Base processing

# === Practical example: Logging hierarchy ===

class BaseHandler:

def handle(self, message):

print(f"BaseHandler: {message}")

class FileHandler(BaseHandler):

def __init__(self, filename):

self.filename = filename

def handle(self, message):

# Write to file

with open(self.filename, 'a') as f:

f.write(f"{message}\n")

# Also call parent handler

super().handle(message)

class EmailHandler(FileHandler):

def __init__(self, filename, email):

super().__init__(filename)

self.email = email

def handle(self, message):

# Send email (simulated)

print(f"Sending email to {self.email}: {message}")

# Call parent (which logs to file and console)

super().handle(message)

handler = EmailHandler('app.log', '[email protected]')

handler.handle("Error occurred")

# Output:

# Sending email to [email protected]: Error occurred

# BaseHandler: Error occurred

# (Also writes to file)

# === super() with **kwargs ===

class A:

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

self.a_value = kwargs.get('a_value', 'default_a')

print(f"A.__init__: a_value={self.a_value}")

super().__init__(**kwargs)

class B:

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

self.b_value = kwargs.get('b_value', 'default_b')

print(f"B.__init__: b_value={self.b_value}")

super().__init__(**kwargs)

class C(A, B):

def __init__(self, c_value, **kwargs):

self.c_value = c_value

print(f"C.__init__: c_value={c_value}")

super().__init__(**kwargs)

obj = C('c_val', a_value='a_val', b_value='b_val')

# Output:

# C.__init__: c_value=c_val

# A.__init__: a_value=a_val

# B.__init__: b_value=b_valMultiple Inheritance and MRO

Multiple inheritance allows classes to inherit from multiple parent classes simultaneously, combining behaviors from different sources. Python uses Method Resolution Order (MRO) based on C3 linearization algorithm to determine which parent method executes when multiple parents define the same method. Understanding MRO prevents confusion in complex inheritance hierarchies, with the diamond problem occurring when a class inherits from two classes that share a common ancestor.

# Multiple Inheritance and MRO

# === Basic multiple inheritance ===

class Flyer:

"""Mixin for flying ability."""

def fly(self):

return "Flying through the air"

class Swimmer:

"""Mixin for swimming ability."""

def swim(self):

return "Swimming through water"

class Duck(Flyer, Swimmer):

"""Duck can both fly and swim."""

def quack(self):

return "Quack!"

duck = Duck()

print(duck.fly()) # Flying through the air (from Flyer)

print(duck.swim()) # Swimming through water (from Swimmer)

print(duck.quack()) # Quack! (from Duck)

# === Method Resolution Order (MRO) ===

class A:

def method(self):

return "A.method"

class B(A):

def method(self):

return "B.method"

class C(A):

def method(self):

return "C.method"

class D(B, C):

pass

# Which method does D use?

d = D()

print(d.method()) # B.method

# Check MRO

print(D.__mro__)

# (<class 'D'>, <class 'B'>, <class 'C'>, <class 'A'>, <class 'object'>)

# Or use mro() method

print(D.mro())

# [<class 'D'>, <class 'B'>, <class 'C'>, <class 'A'>, <class 'object'>]

# === The Diamond Problem ===

class Base:

def __init__(self):

print("Base.__init__")

self.value = "base"

class Left(Base):

def __init__(self):

print("Left.__init__")

super().__init__()

self.left_value = "left"

class Right(Base):

def __init__(self):

print("Right.__init__")

super().__init__()

self.right_value = "right"

class Diamond(Left, Right):

def __init__(self):

print("Diamond.__init__")

super().__init__()

obj = Diamond()

# Output:

# Diamond.__init__

# Left.__init__

# Right.__init__

# Base.__init__

# Base.__init__ called only once (not twice)

# This is MRO at work!

print(Diamond.__mro__)

# (<class 'Diamond'>, <class 'Left'>, <class 'Right'>, <class 'Base'>, <class 'object'>)

# === Cooperative multiple inheritance ===

class Logger:

def log(self, message):

print(f"[LOG] {message}")

class Validator:

def validate(self, data):

print(f"Validating: {data}")

return True

class Processor(Logger, Validator):

def process(self, data):

self.log(f"Processing {data}")

if self.validate(data):

self.log("Processing complete")

return f"Processed: {data}"

else:

self.log("Validation failed")

return None

processor = Processor()

result = processor.process("test_data")

# Output:

# [LOG] Processing test_data

# Validating: test_data

# [LOG] Processing complete

# === MRO with super() ===

class A:

def method(self):

print("A.method")

return "A"

class B(A):

def method(self):

print("B.method")

result = super().method()

return f"B->{result}"

class C(A):

def method(self):

print("C.method")

result = super().method()

return f"C->{result}"

class D(B, C):

def method(self):

print("D.method")

result = super().method()

return f"D->{result}"

d = D()

result = d.method()

print(f"Result: {result}")

# Output:

# D.method

# B.method

# C.method

# A.method

# Result: D->B->C->A

# === Practical example: Mixins ===

class TimestampMixin:

"""Add timestamp functionality."""

def get_timestamp(self):

from datetime import datetime

return datetime.now().strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S')

class LogMixin:

"""Add logging functionality."""

def log(self, message):

print(f"[{self.get_timestamp()}] {message}")

class SaveMixin:

"""Add save functionality."""

def save(self):

print(f"Saving at {self.get_timestamp()}")

class Document(TimestampMixin, LogMixin, SaveMixin):

"""Document with mixed-in functionality."""

def __init__(self, title):

self.title = title

def process(self):

self.log(f"Processing document: {self.title}")

# Do processing

self.save()

self.log("Processing complete")

doc = Document("Report")

doc.process()

# Output:

# [2024-03-15 14:30:45] Processing document: Report

# Saving at 2024-03-15 14:30:45

# [2024-03-15 14:30:45] Processing complete

# === MRO best practices ===

# 1. Check MRO when debugging

print(Document.mro())

# 2. Use super() consistently in all classes

# 3. Keep inheritance hierarchies shallow

# 4. Prefer composition over deep inheritance

# 5. Use mixins for cross-cutting concernsClassName.__mro__ or ClassName.mro() to view Method Resolution Order. This shows the exact order Python searches for methods in multiple inheritance.Inheritance Best Practices

- Prefer composition over inheritance: Use inheritance for is-a relationships (Dog is-a Animal). Use composition for has-a relationships (Car has-a Engine)

- Keep hierarchies shallow: Avoid deep inheritance trees exceeding 3-4 levels. Deep hierarchies become difficult to understand and maintain

- Always use super(): Never call parent methods directly with

Parent.method(self). Usesuper().method()for MRO compatibility - Call super().__init__(): When overriding

__init__, always callsuper().__init__()to ensure proper parent initialization - Use mixins for cross-cutting concerns: Create small mixin classes providing specific functionality (logging, timestamps) that multiple classes can inherit

- Document inheritance relationships: Use docstrings explaining why inheritance is used and what functionality is inherited or overridden

- Check MRO in multiple inheritance: Always verify Method Resolution Order using

__mro__when using multiple inheritance to understand method lookup - Follow Liskov Substitution Principle: Child classes should be substitutable for parent classes without breaking functionality. Override methods to extend, not restrict

- Use abstract base classes: Define interfaces with

abc.ABCand@abstractmethodforcing child classes to implement required methods - Avoid multiple inheritance complexity: Use multiple inheritance sparingly. When needed, use simple mixins rather than complex hierarchies with overlapping methods

Conclusion

Inheritance in Python enables code reuse through child classes deriving from parent classes using class Child(Parent) syntax, automatically inheriting attributes and methods without reimplementation. Single inheritance creates straightforward hierarchies where child classes extend parents adding new attributes in __init__ constructors and new methods providing additional functionality, with isinstance() and issubclass() checking inheritance relationships verifying is-a connections. Method overriding replaces inherited implementations with specialized versions enabling polymorphism where different classes respond identically named methods with class-specific behavior, with child classes defining methods matching parent names causing Python to call child versions when invoked on child instances.

The super() function accesses parent class methods enabling extension rather than replacement, with super().__init__() in child constructors initializing parent state before adding child attributes, and super().method() in overridden methods calling parent implementations adding behavior. Multiple inheritance allows inheriting from multiple parents simultaneously combining behaviors, with Method Resolution Order (MRO) based on C3 linearization determining which parent method executes when multiple parents define identical names, viewable through __mro__ or mro() showing exact search order. The diamond problem occurs when inheritance paths converge on common ancestors, resolved by MRO ensuring each parent initializes exactly once when using super() cooperatively. Best practices emphasize preferring composition over inheritance for has-a relationships, keeping hierarchies shallow avoiding deep nesting exceeding 3-4 levels, always using super() rather than direct parent calls for MRO compatibility, calling super().__init__() ensuring complete initialization, using mixins for cross-cutting concerns like logging or timestamps, documenting inheritance relationships explaining design decisions, checking MRO in multiple inheritance understanding method lookup, following Liskov Substitution Principle ensuring child substitutability, using abstract base classes defining interfaces, and avoiding multiple inheritance complexity preferring simple mixins over complex overlapping hierarchies. By mastering single inheritance establishing clear hierarchies, method overriding customizing behavior, super() function accessing parents properly, multiple inheritance combining behaviors, MRO understanding method resolution, and best practices guiding design decisions, you gain essential tools for code reuse through inheritance, polymorphism supporting consistent interfaces, and hierarchical organization modeling domain relationships supporting maintainable, extensible Python applications from business logic to framework development.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!