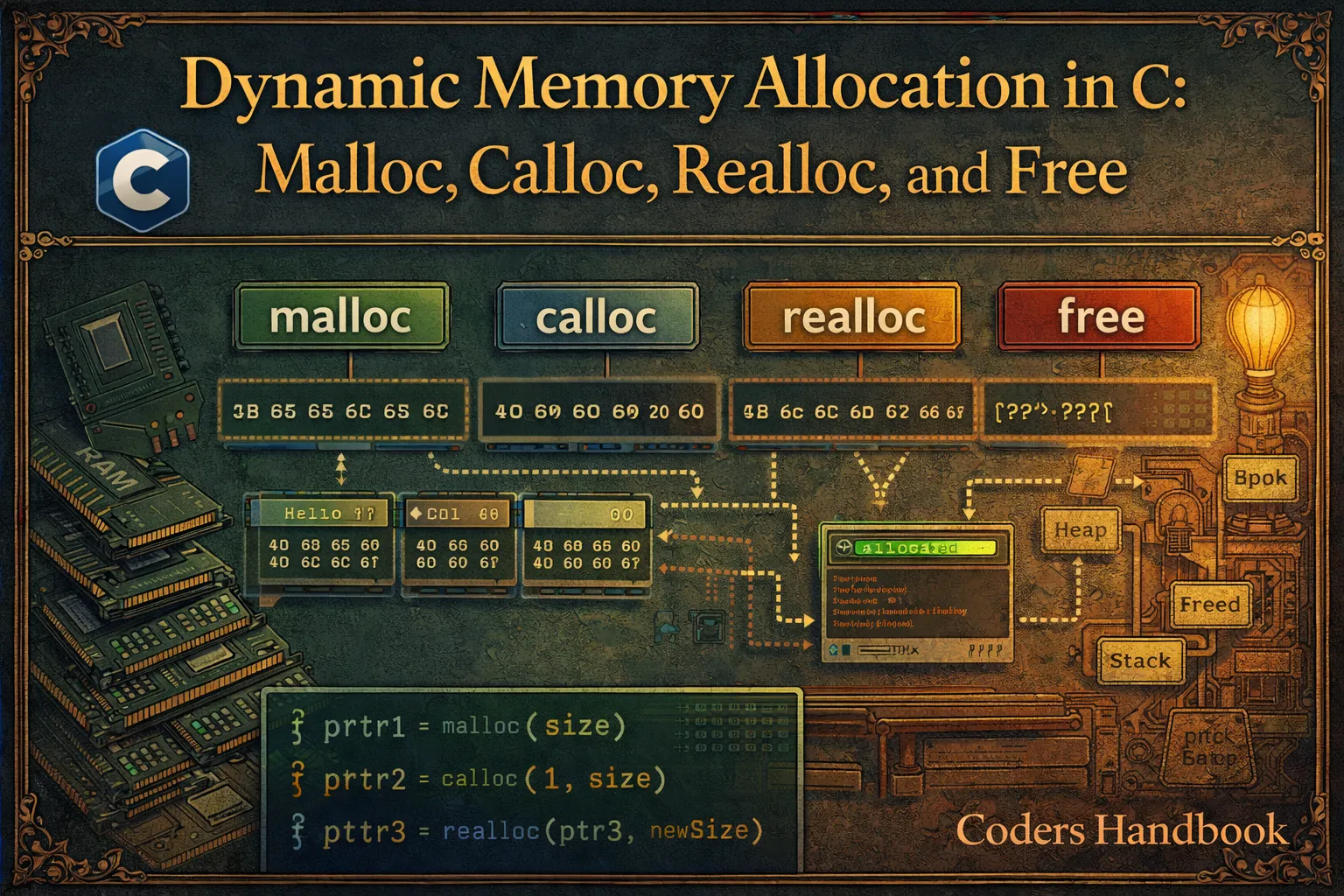

Strings in C: Character Arrays and String Manipulation

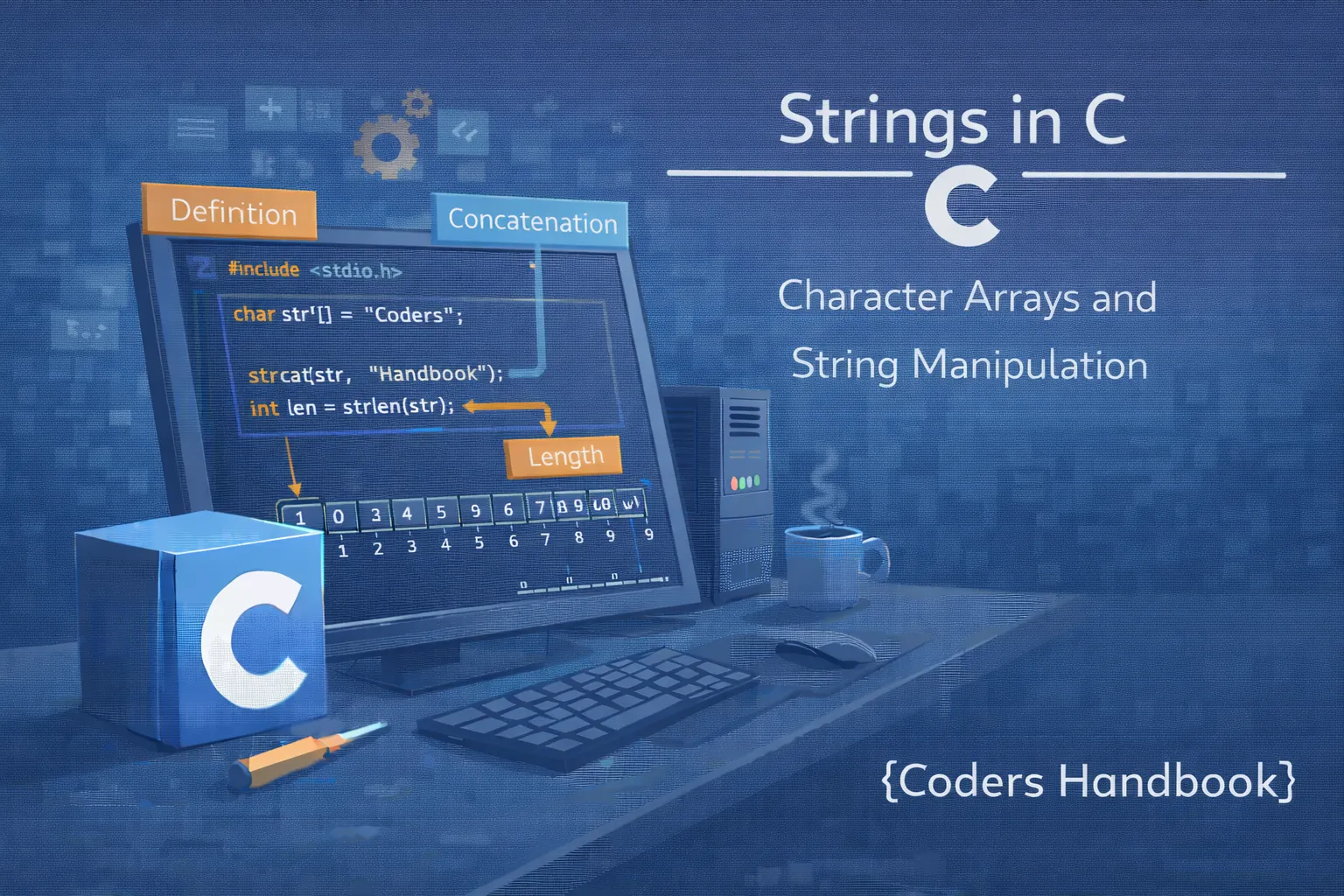

Unlike many modern programming languages that provide a dedicated string data type, C implements strings as arrays of characters terminated by a special null character ('\0') [web:148]. This fundamental design choice makes strings in C both powerful and potentially dangerous—you have complete control over memory and manipulation, but you must also manage termination and bounds checking yourself. Understanding how C strings work at this low level is essential for writing safe, efficient code and avoiding common vulnerabilities like buffer overflows.

This comprehensive guide explores strings as character arrays in C, covering declaration and initialization techniques, the critical importance of null termination, and how to implement basic string operations from scratch without using standard library functions [web:150][web:154]. By mastering these fundamentals, you'll understand exactly how strings work in memory and develop the skills to manipulate them safely and efficiently.

Understanding Strings as Character Arrays

A string in C is simply an array of characters with one crucial distinction: it must end with the null character ('\0', with ASCII value 0) [web:149]. This null terminator signals where the string ends, allowing functions to process strings without needing a separate length parameter. The null character occupies one element of the array, so a string that appears to have 5 characters actually requires 6 bytes of storage.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// String "Hello" requires 6 bytes: 'H','e','l','l','o','\0'

char greeting[6] = "Hello";

// Visualization in memory:

// Index: [0] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

// Value: 'H' 'e' 'l' 'l' 'o' '\0'

// Character array vs String:

char notString[5] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o'}; // NOT a string (no \0)

char actualString[6] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '\0'}; // Valid string

// Printing a string (stops at \0)

printf("%s\n", actualString); // Prints: Hello

// Why null terminator matters:

printf("\nTrying to print array without null terminator:\n");

// printf("%s\n", notString); // DANGEROUS! Will read past array

// Accessing individual characters

printf("First character: %c\n", greeting[0]); // H

printf("Last character before null: %c\n", greeting[4]); // o

printf("Null character (ASCII): %d\n", greeting[5]); // 0

// String is just a character array

printf("\nCharacters in greeting:\n");

for (int i = 0; greeting[i] != '\0'; i++) {

printf("greeting[%d] = '%c' (ASCII: %d)\n", i, greeting[i], greeting[i]);

}

return 0;

}String Declaration and Initialization

C provides several ways to declare and initialize strings, each with specific use cases and considerations [web:151][web:154]. Understanding these methods helps you choose the right approach for different scenarios and avoid common initialization pitfalls.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Method 1: String literal initialization (BEST for known strings)

char name1[] = "Alice"; // Size automatically set to 6 (5 + \0)

char name2[10] = "Bob"; // Size 10, uses 4, rest are \0

// Method 2: Character-by-character initialization

char name3[] = {'J', 'o', 'h', 'n', '\0'}; // MUST include \0

char name4[5] = {'M', 'a', 'r', 'y', '\0'};

// Method 3: Declare now, initialize later

char name5[20]; // Uninitialized - contains garbage!

name5[0] = 'S';

name5[1] = 'a';

name5[2] = 'm';

name5[3] = '\0'; // MUST add null terminator

// Method 4: Initialize to empty string

char empty1[50] = ""; // First element is \0

char empty2[50] = {0}; // All elements are \0

// Method 5: Pointer to string literal

char *message = "Hello, World!"; // Stored in read-only memory

// message[0] = 'h'; // DANGER! Modifying read-only memory

// Print all initialized strings

printf("name1: %s\n", name1);

printf("name2: %s\n", name2);

printf("name3: %s\n", name3);

printf("name4: %s\n", name4);

printf("name5: %s\n", name5);

printf("message: %s\n", message);

// Size considerations

printf("\nSize of name1 array: %zu bytes\n", sizeof(name1)); // 6

printf("Size of name2 array: %zu bytes\n", sizeof(name2)); // 10

// Common mistakes

// char wrong[5] = "Hello"; // ERROR! Needs 6 bytes (5 + \0)

// char bad[]; // ERROR! Must specify size or initialize

return 0;

}The Null Terminator: Why It Matters

The null terminator is what distinguishes a string from a simple character array [web:146][web:149]. String functions rely on this sentinel value to know where processing should stop. Without proper null termination, string functions will continue reading memory beyond the array bounds, leading to unpredictable behavior, crashes, or security vulnerabilities.

#include <stdio.h>

void demonstrateNullTerminator() {

// Properly null-terminated string

char proper[10] = "Hello";

// Memory: ['H']['e']['l']['l']['o']['\0'][0][0][0][0]

// Array without null terminator

char noNull[5] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o'};

// Memory: ['H']['e']['l']['l']['o'] - no \0!

// What happens when we try to print?

printf("Proper string: %s\n", proper); // Works fine

// printf("No null: %s\n", noNull); // DANGEROUS! Undefined behavior

// Manual string processing

printf("\nProcessing proper string:\n");

for (int i = 0; proper[i] != '\0'; i++) {

printf("%c ", proper[i]);

}

printf("\n");

}

void addNullTerminator() {

char buffer[20];

// Manually building a string

buffer[0] = 'T';

buffer[1] = 'e';

buffer[2] = 's';

buffer[3] = 't';

buffer[4] = '\0'; // MUST add this!

printf("Manually created string: %s\n", buffer);

// Common scenario: reading characters one by one

char input[100];

int index = 0;

char ch;

printf("Enter characters (press Enter to finish): ");

while ((ch = getchar()) != '\n' && index < 99) {

input[index++] = ch;

}

input[index] = '\0'; // Critical! Add null terminator

printf("You entered: %s\n", input);

}

int main() {

demonstrateNullTerminator();

printf("\n");

// addNullTerminator(); // Uncomment for interactive demo

return 0;

}String Input and Output

Reading and displaying strings in C requires understanding different input functions and their behaviors. Each function has specific characteristics regarding whitespace handling, buffer safety, and null termination.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char name[50];

char fullName[100];

char line[200];

// Method 1: scanf() - reads until whitespace

printf("Enter your first name: ");

scanf("%s", name); // Note: no & needed for strings!

printf("You entered: %s\n\n", name);

// scanf limitation: stops at first space

// Input: "John Doe" -> stores only "John"

// Method 2: scanf with width specifier (safer)

printf("Enter name (max 49 chars): ");

scanf("%49s", name); // Prevents buffer overflow

printf("Name: %s\n\n", name);

// Clear input buffer

while (getchar() != '\n');

// Method 3: gets() - NEVER USE! (deprecated, unsafe)

// gets(fullName); // DANGEROUS! No bounds checking

// Method 4: fgets() - RECOMMENDED (safe)

printf("Enter full name: ");

fgets(fullName, sizeof(fullName), stdin);

// fgets includes newline - may need to remove it

// Remove trailing newline from fgets

for (int i = 0; fullName[i] != '\0'; i++) {

if (fullName[i] == '\n') {

fullName[i] = '\0';

break;

}

}

printf("Full name: %s\n\n", fullName);

// Method 5: Character-by-character input

printf("Enter a line (press Enter to finish): ");

int i = 0;

char ch;

while ((ch = getchar()) != '\n' && i < 199) {

line[i++] = ch;

}

line[i] = '\0'; // Add null terminator

printf("Line: %s\n", line);

// Output methods

printf("\nOutput methods:\n");

printf("%s\n", name); // printf with %s

puts(name); // puts (adds newline)

// Character-by-character output

for (i = 0; name[i] != '\0'; i++) {

putchar(name[i]);

}

putchar('\n');

return 0;

}String Operations Without Library Functions

Implementing string operations manually helps you understand exactly how they work and prepares you for situations where library functions aren't available [web:150]. These implementations demonstrate fundamental string manipulation techniques using only character array operations.

#include <stdio.h>

// Calculate string length (like strlen)

int stringLength(char str[]) {

int length = 0;

while (str[length] != '\0') {

length++;

}

return length;

}

// Copy string (like strcpy)

void stringCopy(char dest[], char src[]) {

int i = 0;

while (src[i] != '\0') {

dest[i] = src[i];

i++;

}

dest[i] = '\0'; // Don't forget null terminator!

}

// Concatenate strings (like strcat)

void stringConcat(char dest[], char src[]) {

int i = 0, j = 0;

// Find end of dest string

while (dest[i] != '\0') {

i++;

}

// Copy src to end of dest

while (src[j] != '\0') {

dest[i] = src[j];

i++;

j++;

}

dest[i] = '\0'; // Add null terminator

}

// Compare strings (like strcmp)

int stringCompare(char str1[], char str2[]) {

int i = 0;

while (str1[i] != '\0' && str2[i] != '\0') {

if (str1[i] != str2[i]) {

return str1[i] - str2[i]; // Difference in ASCII values

}

i++;

}

// If we reach here, one or both strings ended

return str1[i] - str2[i];

}

int main() {

char str1[50] = "Hello";

char str2[50];

char str3[100] = "Good ";

// Test length

int len = stringLength(str1);

printf("Length of '%s': %d\n\n", str1, len);

// Test copy

stringCopy(str2, str1);

printf("Original: %s\n", str1);

printf("Copy: %s\n\n", str2);

// Test concatenation

stringConcat(str3, "Morning");

printf("Concatenated: %s\n\n", str3);

// Test comparison

char s1[] = "Apple";

char s2[] = "Banana";

char s3[] = "Apple";

printf("Comparing '%s' and '%s': %d\n", s1, s2, stringCompare(s1, s2));

printf("Comparing '%s' and '%s': %d\n", s1, s3, stringCompare(s1, s3));

printf("(0 means equal, <0 means first < second, >0 means first > second)\n");

return 0;

}Advanced String Manipulation

Beyond basic operations, string manipulation includes reversing, case conversion, searching, and character counting. These operations build on the fundamental techniques and demonstrate practical string processing algorithms.

#include <stdio.h>

// Reverse a string in place

void reverseString(char str[]) {

int start = 0;

int end = 0;

// Find end of string

while (str[end] != '\0') {

end++;

}

end--; // Point to last character, not \0

// Swap characters from outside to inside

while (start < end) {

char temp = str[start];

str[start] = str[end];

str[end] = temp;

start++;

end--;

}

}

// Convert to uppercase

void toUpperCase(char str[]) {

for (int i = 0; str[i] != '\0'; i++) {

if (str[i] >= 'a' && str[i] <= 'z') {

str[i] = str[i] - 32; // ASCII 'a' to 'A' is -32

}

}

}

// Convert to lowercase

void toLowerCase(char str[]) {

for (int i = 0; str[i] != '\0'; i++) {

if (str[i] >= 'A' && str[i] <= 'Z') {

str[i] = str[i] + 32; // ASCII 'A' to 'a' is +32

}

}

}

// Count vowels

int countVowels(char str[]) {

int count = 0;

for (int i = 0; str[i] != '\0'; i++) {

char ch = str[i];

if (ch == 'a' || ch == 'e' || ch == 'i' || ch == 'o' || ch == 'u' ||

ch == 'A' || ch == 'E' || ch == 'I' || ch == 'O' || ch == 'U') {

count++;

}

}

return count;

}

// Check if palindrome

int isPalindrome(char str[]) {

int start = 0, end = 0;

// Find end

while (str[end] != '\0') end++;

end--;

// Compare from both ends

while (start < end) {

if (str[start] != str[end]) {

return 0; // Not palindrome

}

start++;

end--;

}

return 1; // Is palindrome

}

// Find substring

int findSubstring(char str[], char substr[]) {

for (int i = 0; str[i] != '\0'; i++) {

int j = 0;

int k = i;

// Check if substring matches starting at position i

while (substr[j] != '\0' && str[k] == substr[j]) {

j++;

k++;

}

if (substr[j] == '\0') {

return i; // Found at position i

}

}

return -1; // Not found

}

int main() {

char text[100] = "Hello World";

printf("Original: %s\n", text);

// Reverse

char rev[100] = "Reverse";

reverseString(rev);

printf("Reversed 'Reverse': %s\n", rev);

// Case conversion

char upper[100] = "convert me";

toUpperCase(upper);

printf("Uppercase: %s\n", upper);

char lower[100] = "CONVERT ME";

toLowerCase(lower);

printf("Lowercase: %s\n", lower);

// Count vowels

int vowels = countVowels(text);

printf("Vowels in '%s': %d\n", text, vowels);

// Palindrome check

char pal1[] = "radar";

char pal2[] = "hello";

printf("%s is %sa palindrome\n", pal1, isPalindrome(pal1) ? "" : "not ");

printf("%s is %sa palindrome\n", pal2, isPalindrome(pal2) ? "" : "not ");

// Substring search

int pos = findSubstring(text, "World");

if (pos != -1) {

printf("'World' found at position %d\n", pos);

}

return 0;

}Common String Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Working with C strings involves several common pitfalls that can lead to bugs, crashes, or security vulnerabilities. Understanding these issues helps you write safer string handling code.

- Buffer Overflow: Writing beyond array bounds when string is too long—always validate input size and use bounded functions

- Missing Null Terminator: Forgetting '\0' when building strings manually—causes functions to read garbage memory

- Off-by-One Errors: Allocating exactly strlen(str) instead of strlen(str)+1—no room for null terminator

- Modifying String Literals: Attempting to change strings like

char *s = "text"—causes undefined behavior - Uninitialized Arrays: Using character arrays without initialization—contains random garbage values

- Using gets(): This unsafe function has no bounds checking—always use fgets() instead

- Forgetting Array vs Pointer:

sizeof()behaves differently—gives array size vs pointer size

Best Practices for String Handling

Following best practices ensures your string code is safe, maintainable, and efficient. These guidelines help prevent common errors and security vulnerabilities.

- Always allocate n+1 bytes: For an n-character string, allocate space for the null terminator

- Validate input length: Check string length before copying to prevent buffer overflows

- Use bounded functions: Prefer

strncpy()overstrcpy(),fgets()overgets() - Initialize arrays: Set arrays to empty string

""or zero{0}before use - Check null termination: After manual string operations, verify '\0' is present

- Use const for read-only: Mark string parameters as

const char*if function doesn't modify them - Document assumptions: Comment maximum string lengths and buffer sizes clearly

- Test edge cases: Verify behavior with empty strings, maximum length, and special characters

malloc() and remember to free() the memory when done.Conclusion

Strings in C are character arrays with a critical requirement: the null terminator ('\0') that marks where the string ends. This fundamental design gives you complete control over string manipulation but requires careful attention to buffer sizes, null termination, and bounds checking. Understanding how strings work at this low level—as sequences of characters stored contiguously in memory—is essential for writing safe, efficient C code.

By implementing string operations from scratch—calculating length, copying, concatenating, comparing, and manipulating characters—you develop deep understanding of how string functions actually work. Remember to always allocate space for the null terminator, use bounded input functions like fgets() instead of unsafe alternatives, and validate string lengths before operations. These practices prevent buffer overflows and undefined behavior that plague C programs. Master these string fundamentals, and you'll have the foundation needed for text processing, file handling, and all string-related programming tasks in C.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!