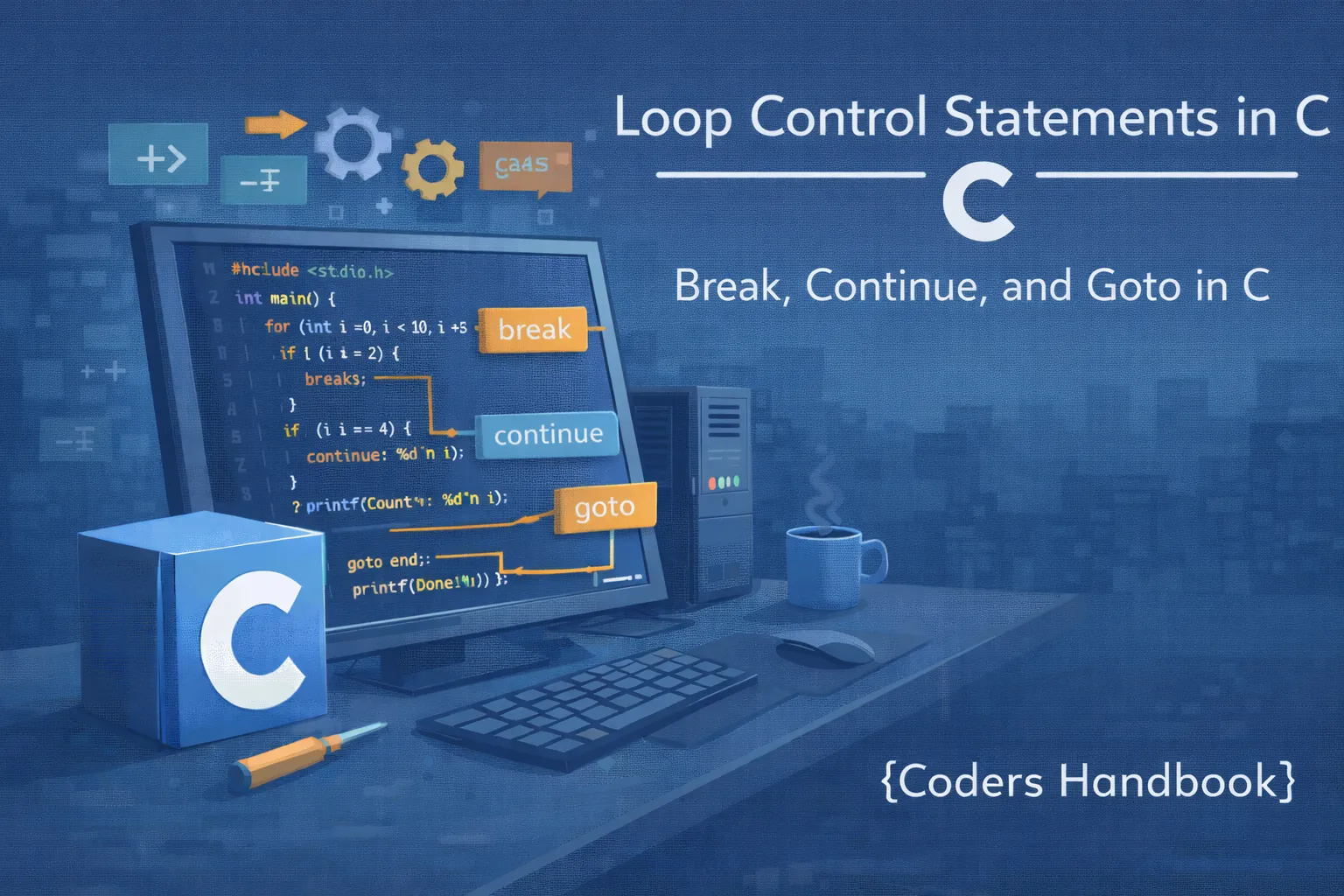

Loop Control Statements: Break, Continue, and Goto in C

Loop control statements are powerful tools that alter the normal flow of program execution, allowing you to exit loops prematurely, skip iterations, or jump to specific code locations [web:56]. While loops execute repetitively based on conditions, control statements give you fine-grained control over exactly when and how iterations occur. Understanding these statements—break, continue, and goto—is essential for writing sophisticated control flow logic and handling complex scenarios that don't fit standard looping patterns.

These jump statements modify the sequential execution of code, enabling early termination, selective iteration skipping, and unconventional program flow [web:63]. However, with great power comes responsibility—improper use, particularly of goto, can create confusing, unmaintainable code. This comprehensive guide explores each control statement with practical examples, best practices, and guidance on when each approach is appropriate.

The Break Statement: Immediate Loop Termination

The break statement immediately terminates the enclosing loop or switch statement and transfers control to the first statement following that construct [web:58][web:64]. When break executes, the program exits the loop entirely—regardless of whether the loop condition is still true or how many iterations remain. This makes break invaluable for scenarios where you've found what you're searching for, encountered an error condition, or reached a logical endpoint before the loop would naturally terminate.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Example 1: Search and exit when found

int numbers[] = {10, 23, 45, 67, 89, 12, 34};

int searchValue = 67;

int found = 0;

printf("Searching for %d in array...\n", searchValue);

for (int i = 0; i < 7; i++) {

if (numbers[i] == searchValue) {

printf("Found %d at index %d\n", searchValue, i);

found = 1;

break; // Exit loop immediately after finding

}

}

if (!found) {

printf("Value not found\n");

}

// Example 2: User input validation with early exit

printf("\nEnter positive numbers (0 to quit):\n");

int sum = 0;

int num;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

printf("Enter number %d: ", i + 1);

scanf("%d", &num);

if (num == 0) {

printf("Zero entered. Exiting...\n");

break; // Exit when sentinel value entered

}

if (num < 0) {

printf("Negative number! Stopping input.\n");

break; // Exit on invalid input

}

sum += num;

}

printf("Total sum: %d\n", sum);

return 0;

}The break statement can only be used within loop statements (for, while, do-while) or switch statements [web:58]. If you use break with an if statement, that if must be nested inside a loop or switch for break to be valid. When used in nested loops, break only exits the innermost loop containing it—not all loops [web:61].

The Continue Statement: Skip to Next Iteration

Unlike break which exits the loop entirely, the continue statement skips the remaining code in the current iteration and immediately jumps to the next iteration [web:59][web:64]. The loop continues executing—only the current iteration's remaining statements are bypassed. This is perfect for filtering data, skipping invalid values, or processing only elements that meet specific criteria without exiting the entire loop.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Example 1: Print only odd numbers

printf("Odd numbers from 1 to 10:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) {

continue; // Skip even numbers

}

printf("%d ", i);

}

printf("\n\n");

// Example 2: Skip specific values

printf("Numbers 1-20 except multiples of 5:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 20; i++) {

if (i % 5 == 0) {

continue; // Skip multiples of 5

}

printf("%d ", i);

}

printf("\n\n");

// Example 3: Process only valid data

int scores[] = {85, -1, 92, 78, -1, 88, 95, -1};

int validCount = 0;

int total = 0;

printf("Processing valid scores:\n");

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

if (scores[i] < 0) {

printf("Skipping invalid score at index %d\n", i);

continue; // Skip invalid scores

}

printf("Valid score: %d\n", scores[i]);

total += scores[i];

validCount++;

}

if (validCount > 0) {

printf("Average of valid scores: %.2f\n", (float)total / validCount);

}

return 0;

}When continue executes, the program control jumps to the loop's update expression (in for loops) or back to the condition test (in while and do-while loops) [web:60]. The continue statement can only be used within looping statements, not in switch statements. Like break, if continue appears in an if statement, that if must be inside a loop [web:58].

Break vs Continue: Understanding the Difference

While both break and continue alter normal loop flow, they serve fundamentally different purposes [web:60]. Break terminates the loop completely, while continue only skips the current iteration. Understanding this distinction is crucial for choosing the right statement for your specific needs.

| Feature | Break Statement | Continue Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Exits loop immediately | Skips to next iteration |

| Loop Execution | Terminates completely | Continues with next iteration |

| Remaining Code | Skipped entirely | Skipped only for current iteration |

| Use in Switch | Yes (required after cases) | No (compile error) |

| Common Use Case | Search found, error detected | Filter data, skip invalid values |

| Control Transfer | To statement after loop | To loop condition/update |

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Demonstrating break vs continue

printf("Using BREAK - exits at 5:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i == 5) {

break; // Loop ends at 5

}

printf("%d ", i);

}

printf("\nLoop terminated\n\n");

printf("Using CONTINUE - skips 5:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i == 5) {

continue; // Only skips 5, continues to 6-10

}

printf("%d ", i);

}

printf("\nLoop completed\n\n");

// You can use both in the same loop

printf("Using BOTH - skip evens, exit at 15:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 20; i++) {

if (i > 15) {

break; // Exit when exceeding 15

}

if (i % 2 == 0) {

continue; // Skip even numbers

}

printf("%d ", i);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}Nested Loops and Control Statements

When working with nested loops, understanding how break and continue affect loop control becomes more complex. Both statements only affect the innermost loop in which they appear [web:61]. To control outer loops, you need additional techniques such as flag variables, goto statements, or restructuring your code with functions.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Break in nested loops - only breaks inner loop

printf("Break in nested loops:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 3; i++) {

printf("Outer loop i=%d: ", i);

for (int j = 1; j <= 5; j++) {

if (j == 4) {

break; // Only exits inner loop

}

printf("%d ", j);

}

printf("\n");

}

printf("\n");

// Using flag to break outer loop

printf("Breaking outer loop with flag:\n");

int found = 0;

for (int i = 1; i <= 5 && !found; i++) {

for (int j = 1; j <= 5; j++) {

printf("(%d,%d) ", i, j);

if (i * j > 10) {

printf("\nProduct > 10 found!\n");

found = 1;

break; // Break inner loop

}

}

if (found) {

break; // Break outer loop

}

}

printf("\n");

// Continue in nested loops

printf("Continue in nested loops:\n");

for (int i = 1; i <= 3; i++) {

for (int j = 1; j <= 5; j++) {

if (j == 3) {

continue; // Skip j=3 in inner loop only

}

printf("(%d,%d) ", i, j);

}

printf("\n");

}

return 0;

}The Goto Statement: Unconditional Jump

The goto statement provides an unconditional jump to a labeled statement anywhere in the same function [web:56]. Unlike break and continue which have specific, predictable behaviors, goto can jump to any labeled location, forward or backward. This flexibility makes goto simultaneously powerful and dangerous—it can solve specific problems elegantly but can also create unreadable, unmaintainable code when misused [web:65].

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

// Basic goto syntax

int choice;

menu:

printf("\n=== Simple Menu ===\n");

printf("1. Option One\n");

printf("2. Option Two\n");

printf("3. Exit\n");

printf("Enter choice: ");

scanf("%d", &choice);

if (choice == 1) {

printf("You selected Option One\n");

goto menu; // Jump back to menu

} else if (choice == 2) {

printf("You selected Option Two\n");

goto menu;

} else if (choice == 3) {

printf("Exiting...\n");

goto end; // Jump to end

} else {

printf("Invalid choice!\n");

goto menu;

}

end:

printf("Program terminated\n");

return 0;

}Legitimate Uses of Goto

Despite its controversial reputation, goto has legitimate use cases in C programming [web:62]. The most accepted uses are breaking out of deeply nested loops and implementing centralized error handling and cleanup code [web:65]. Even the Linux kernel uses goto judiciously for these purposes, demonstrating that goto isn't inherently bad—only its misuse is problematic.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

// Legitimate use case 1: Breaking nested loops

void searchMatrix() {

int matrix[3][3] = {{1,2,3}, {4,5,6}, {7,8,9}};

int target = 5;

int found = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

if (matrix[i][j] == target) {

printf("Found %d at position (%d, %d)\n", target, i, j);

found = 1;

goto exit_loops; // Clean exit from nested loops

}

}

}

exit_loops:

if (!found) {

printf("Value not found\n");

}

}

// Legitimate use case 2: Error handling and cleanup

int processFile(const char* filename) {

FILE *file1 = NULL, *file2 = NULL;

char *buffer = NULL;

int result = 0;

file1 = fopen(filename, "r");

if (file1 == NULL) {

printf("Error opening file1\n");

goto cleanup;

}

buffer = (char*)malloc(1024);

if (buffer == NULL) {

printf("Memory allocation failed\n");

goto cleanup;

}

file2 = fopen("output.txt", "w");

if (file2 == NULL) {

printf("Error opening file2\n");

goto cleanup;

}

// Process files...

printf("Processing files successfully\n");

result = 1;

cleanup:

// Centralized cleanup - always executes

if (file1) fclose(file1);

if (file2) fclose(file2);

if (buffer) free(buffer);

return result;

}

int main() {

searchMatrix();

processFile("data.txt");

return 0;

}When to Use Goto

- Breaking deeply nested loops: When you need to exit multiple loop levels simultaneously

- Centralized error handling: Jumping to cleanup code from multiple error conditions

- Resource cleanup: Ensuring file handles, memory, and connections are properly released

- State machine implementation: Jumping between different states in complex logic

Why Goto Should Be Avoided

The primary criticism of goto is that it creates "spaghetti code"—tangled, difficult-to-follow program logic where execution jumps unpredictably [web:65]. Using goto excessively reduces code readability, makes debugging harder, and violates structured programming principles. Modern programming paradigms emphasize clear, linear flow with well-defined entry and exit points, which goto can undermine [web:62].

- Reduces readability: Breaks the natural top-to-bottom code flow, making logic harder to follow

- Creates spaghetti code: Multiple goto statements create tangled, unmaintainable code paths

- Harder debugging: Control flow is unpredictable, making it difficult to trace execution

- Violates structured programming: Undermines principles of modularity and clear program structure

- Error-prone: Easy to create infinite loops or skip critical initialization code

- Better alternatives exist: Functions, loops, and flags usually provide clearer solutions

Best Practices for Loop Control

Using loop control statements effectively requires discipline and adherence to best practices [web:65]. These guidelines help you leverage the power of break, continue, and goto while maintaining code quality and readability.

- Prefer break and continue: Use these instead of goto whenever possible for loop control

- Use clear conditions: Make break and continue conditions obvious and well-commented

- Limit goto usage: Reserve goto only for the specific cases where it provides clear benefits

- Document goto jumps: Always comment why goto is necessary and where it jumps

- Use descriptive labels: Labels like

cleanup:orerror_exit:are clearer thanlabel1: - Forward jumps only: Avoid jumping backwards with goto as it can create confusing loops

- Consider refactoring: If you need complex control flow, consider extracting code into functions

Conclusion

Loop control statements—break, continue, and goto—are powerful tools for managing program flow in C. The break statement provides clean loop termination when you've achieved your goal or encountered an error. The continue statement enables selective iteration skipping, perfect for filtering data or handling special cases. While goto can solve specific problems like multi-level loop breaks and centralized error handling, it should be used sparingly and only when clearer alternatives aren't available.

Understanding when and how to use each statement transforms you from writing rigid, inflexible loops to crafting sophisticated control flow that handles complex scenarios elegantly. Remember that break and continue are your primary tools for loop control, while goto should be reserved for exceptional cases where it genuinely improves code clarity. By following best practices and choosing the right control statement for each situation, you'll write more maintainable, professional C code that other developers can easily understand and modify.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!