Command Line Arguments in C: argc and argv Explained

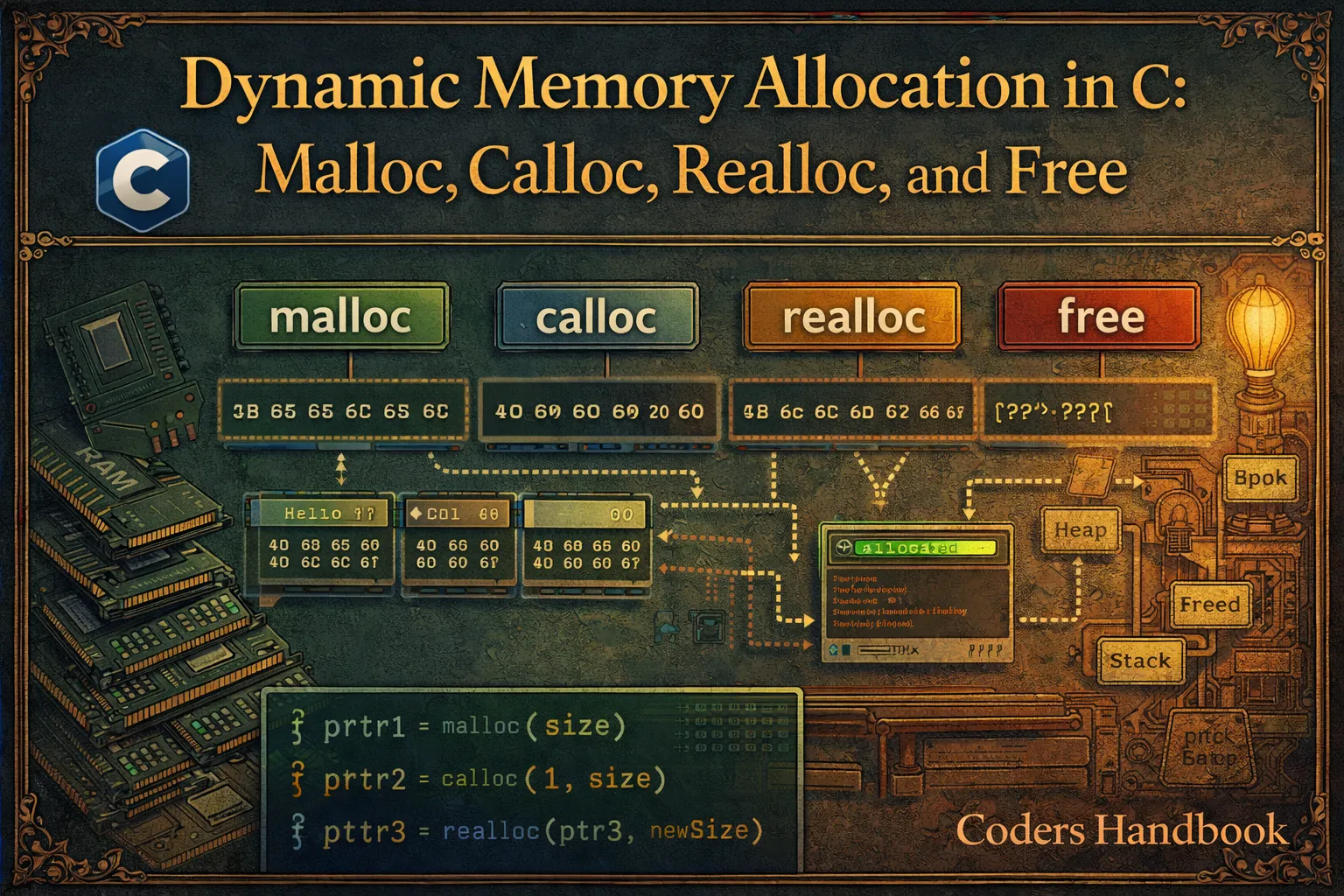

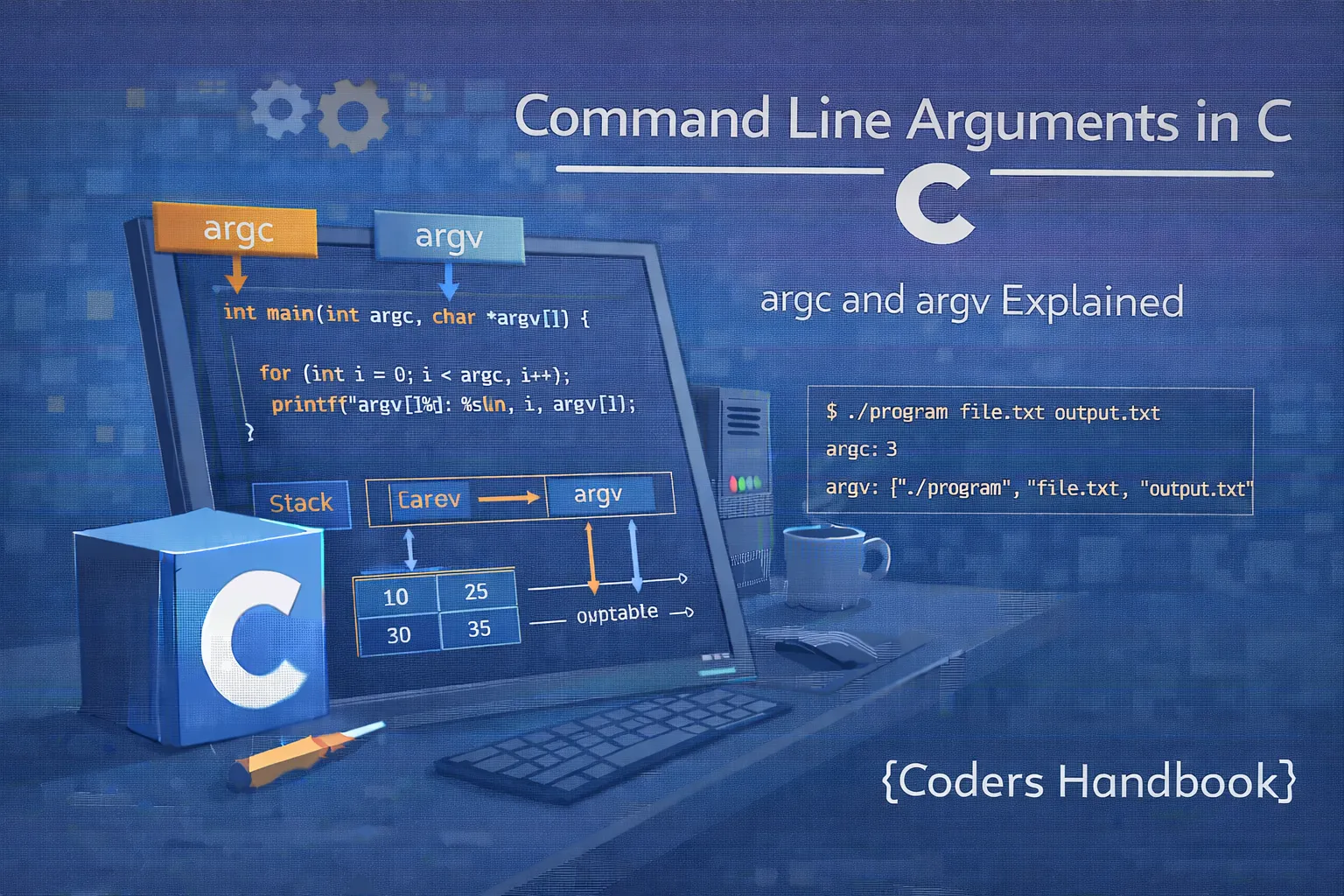

Command-line arguments enable programs to accept input directly from the terminal when launched, allowing users to customize behavior, specify files, set options, and pass data without requiring interactive prompts [web:303][web:304]. In C, the main function can accept two special parameters—argc (argument count) representing the total number of arguments including the program name, and argv (argument vector) which is an array of character pointers containing the actual argument strings [web:306][web:307]. This mechanism is fundamental to building flexible command-line utilities, system tools, and automation scripts that integrate seamlessly with shell environments and batch processing workflows. Understanding argc and argv is essential for creating professional-grade programs that follow Unix philosophy of small, composable tools.

This comprehensive guide explores command-line argument handling from fundamentals to advanced techniques, covering how argc and argv work together, accessing individual arguments, converting string arguments to numeric types, validating user input, building practical command-line tools like file processors and calculators, implementing option flags and switches, parsing complex argument patterns, and following best practices for robust argument handling [web:312]. Mastering these concepts enables you to create powerful utilities that behave like professional Unix tools such as grep, ls, and git.

Understanding argc and argv

The main function signature int main(int argc, char *argv[]) or equivalently int main(int argc, char **argv) defines two parameters that capture command-line arguments [web:303][web:309]. The argc parameter holds the count of arguments passed to the program, always being at least 1 since argv[0] contains the program name itself, while argv is an array of strings where each element points to a null-terminated character string representing one argument.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("=== Understanding argc and argv ===\n\n");

// argc: Argument Count

// - Total number of command-line arguments

// - Always >= 1 (program name is argv[0])

// - Type: int

// argv: Argument Vector

// - Array of character pointers (strings)

// - argv[0]: Program name/path

// - argv[1] to argv[argc-1]: Actual arguments

// - argv[argc]: NULL (sentinel value)

// - Type: char *argv[] or char **argv

printf("Number of arguments: %d\n\n", argc);

// Display all arguments

printf("Arguments:\n");

for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) {

printf(" argv[%d] = \"%s\"\n", i, argv[i]);

}

// Example terminal commands and their argc/argv:

// Command: ./program

// argc = 1

// argv[0] = "./program"

// Command: ./program hello world

// argc = 3

// argv[0] = "./program"

// argv[1] = "hello"

// argv[2] = "world"

// Command: ./program file.txt -v --output result.txt

// argc = 5

// argv[0] = "./program"

// argv[1] = "file.txt"

// argv[2] = "-v"

// argv[3] = "--output"

// argv[4] = "result.txt"

return 0;

}

// Compile: gcc program.c -o program

// Run: ./program arg1 arg2 arg3Accessing and Processing Arguments

Processing command-line arguments involves iterating through the argv array and handling each argument appropriately [web:307]. Since all arguments are passed as strings, programs must convert them to appropriate types when numeric or other data types are needed, using functions like atoi, atof, or strtol for safe conversion.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("=== Accessing Arguments ===\n\n");

// Method 1: Index-based access

if (argc > 1) {

printf("First argument: %s\n", argv[1]);

}

if (argc > 2) {

printf("Second argument: %s\n", argv[2]);

}

// Method 2: Loop through all arguments

printf("\nAll arguments using for loop:\n");

for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) {

printf(" Argument %d: %s\n", i, argv[i]);

}

// Method 3: Skip program name (start from index 1)

printf("\nUser-provided arguments only:\n");

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

printf(" %s\n", argv[i]);

}

// Method 4: Pointer arithmetic (alternative)

printf("\nUsing pointer arithmetic:\n");

char **ptr = argv;

while (*ptr) {

printf(" %s\n", *ptr);

ptr++;

}

// Checking specific arguments

printf("\n=== Argument Checking ===\n\n");

if (argc < 2) {

printf("No arguments provided\n");

printf("Usage: %s <argument1> <argument2> ...\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

// Check for specific argument

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

if (strcmp(argv[i], "--help") == 0 || strcmp(argv[i], "-h") == 0) {

printf("Help requested!\n");

printf("This program processes command-line arguments.\n");

return 0;

}

}

return 0;

}

// Example usage:

// ./program hello world

// ./program --help

// ./program file1.txt file2.txt -vConverting String Arguments to Other Types

Command-line arguments arrive as strings regardless of their intended type, requiring explicit conversion for numeric processing [web:307]. C provides several conversion functions: atoi for integers, atof for floating-point numbers, and strtol/strtod for safer conversion with error checking through the detection of invalid characters.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("=== Converting Arguments ===\n\n");

if (argc < 4) {

printf("Usage: %s <integer> <float> <string>\n", argv[0]);

printf("Example: %s 42 3.14 hello\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

// Method 1: Using atoi (simple but no error checking)

int num1 = atoi(argv[1]);

printf("Integer (atoi): %d\n", num1);

// Method 2: Using strtol (safer with error checking)

char *endptr;

errno = 0;

long num2 = strtol(argv[1], &endptr, 10);

if (errno != 0) {

perror("strtol");

return 1;

}

if (endptr == argv[1]) {

printf("Error: No digits found in '%s'\n", argv[1]);

return 1;

}

if (*endptr != '\0') {

printf("Warning: Extra characters after number: '%s'\n", endptr);

}

printf("Integer (strtol): %ld\n", num2);

// Converting floating-point

double fnum1 = atof(argv[2]);

printf("\nFloat (atof): %.2f\n", fnum1);

// Using strtod (safer)

errno = 0;

double fnum2 = strtod(argv[2], &endptr);

if (errno != 0) {

perror("strtod");

return 1;

}

if (endptr == argv[2]) {

printf("Error: No valid number found\n");

return 1;

}

printf("Float (strtod): %.2f\n", fnum2);

// String arguments (no conversion needed)

printf("\nString: %s\n", argv[3]);

// Validation examples

printf("\n=== Validation ===\n\n");

// Check if argument is numeric

int isNumeric = 1;

for (char *p = argv[1]; *p; p++) {

if (*p < '0' || *p > '9') {

if (p == argv[1] && (*p == '-' || *p == '+')) {

continue; // Allow leading sign

}

isNumeric = 0;

break;

}

}

printf("%s is %s\n", argv[1], isNumeric ? "numeric" : "not numeric");

return 0;

}

// Example usage:

// ./program 123 45.67 text

// ./program abc 3.14 hello (will show error for 'abc')Building a Simple Calculator Tool

A practical example demonstrates command-line argument handling by building a calculator that accepts an operation and numbers as arguments. This showcases argument validation, type conversion, and providing helpful usage messages when arguments are incorrect.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

void printUsage(const char *programName) {

printf("Usage: %s <operation> <num1> <num2>\n", programName);

printf("\nOperations:\n");

printf(" add - Addition\n");

printf(" sub - Subtraction\n");

printf(" mul - Multiplication\n");

printf(" div - Division\n");

printf("\nExample:\n");

printf(" %s add 10 5\n", programName);

printf(" %s mul 3.5 2\n", programName);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// Validate argument count

if (argc != 4) {

printf("Error: Invalid number of arguments\n\n");

printUsage(argv[0]);

return 1;

}

// Get operation

char *operation = argv[1];

// Convert arguments to numbers

char *endptr;

double num1 = strtod(argv[2], &endptr);

if (*endptr != '\0') {

printf("Error: '%s' is not a valid number\n", argv[2]);

return 1;

}

double num2 = strtod(argv[3], &endptr);

if (*endptr != '\0') {

printf("Error: '%s' is not a valid number\n", argv[3]);

return 1;

}

// Perform calculation

double result;

int validOperation = 1;

if (strcmp(operation, "add") == 0) {

result = num1 + num2;

printf("%.2f + %.2f = %.2f\n", num1, num2, result);

}

else if (strcmp(operation, "sub") == 0) {

result = num1 - num2;

printf("%.2f - %.2f = %.2f\n", num1, num2, result);

}

else if (strcmp(operation, "mul") == 0) {

result = num1 * num2;

printf("%.2f * %.2f = %.2f\n", num1, num2, result);

}

else if (strcmp(operation, "div") == 0) {

if (num2 == 0) {

printf("Error: Division by zero\n");

return 1;

}

result = num1 / num2;

printf("%.2f / %.2f = %.2f\n", num1, num2, result);

}

else {

printf("Error: Unknown operation '%s'\n\n", operation);

printUsage(argv[0]);

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

// Compile: gcc calculator.c -o calc

// Usage examples:

// ./calc add 10 5 → Output: 10.00 + 5.00 = 15.00

// ./calc mul 3.5 2 → Output: 3.50 * 2.00 = 7.00

// ./calc div 10 0 → Output: Error: Division by zero

// ./calc power 2 3 → Output: Error: Unknown operation 'power'Implementing Option Flags and Switches

Professional command-line tools use option flags (like -v for verbose or --help for help text) to modify behavior [web:304]. Implementing flags requires checking arguments for specific prefixes and handling both short-form (-v) and long-form (--verbose) options, typically using string comparison functions.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

typedef struct {

bool verbose;

bool quiet;

bool force;

char *inputFile;

char *outputFile;

} Options;

void printHelp(const char *programName) {

printf("Usage: %s [OPTIONS] <input_file>\n", programName);

printf("\nOptions:\n");

printf(" -v, --verbose Enable verbose output\n");

printf(" -q, --quiet Suppress output\n");

printf(" -f, --force Force overwrite\n");

printf(" -o, --output Specify output file\n");

printf(" -h, --help Display this help\n");

printf("\nExamples:\n");

printf(" %s input.txt\n", programName);

printf(" %s -v -o output.txt input.txt\n", programName);

printf(" %s --verbose --force input.txt\n", programName);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

Options opts = {false, false, false, NULL, NULL};

// Parse arguments

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

// Short options

if (strcmp(argv[i], "-v") == 0) {

opts.verbose = true;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "-q") == 0) {

opts.quiet = true;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "-f") == 0) {

opts.force = true;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "-h") == 0) {

printHelp(argv[0]);

return 0;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "-o") == 0) {

if (i + 1 < argc) {

opts.outputFile = argv[++i];

} else {

printf("Error: -o requires an argument\n");

return 1;

}

}

// Long options

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "--verbose") == 0) {

opts.verbose = true;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "--quiet") == 0) {

opts.quiet = true;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "--force") == 0) {

opts.force = true;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "--help") == 0) {

printHelp(argv[0]);

return 0;

}

else if (strcmp(argv[i], "--output") == 0) {

if (i + 1 < argc) {

opts.outputFile = argv[++i];

} else {

printf("Error: --output requires an argument\n");

return 1;

}

}

// Positional argument (input file)

else if (argv[i][0] != '-') {

if (opts.inputFile == NULL) {

opts.inputFile = argv[i];

} else {

printf("Error: Multiple input files specified\n");

return 1;

}

}

// Unknown option

else {

printf("Error: Unknown option '%s'\n\n", argv[i]);

printHelp(argv[0]);

return 1;

}

}

// Validate required arguments

if (opts.inputFile == NULL) {

printf("Error: Input file required\n\n");

printHelp(argv[0]);

return 1;

}

// Display parsed options

printf("\n=== Parsed Options ===\n\n");

printf("Input file: %s\n", opts.inputFile);

printf("Output file: %s\n", opts.outputFile ? opts.outputFile : "(none)");

printf("Verbose: %s\n", opts.verbose ? "Yes" : "No");

printf("Quiet: %s\n", opts.quiet ? "Yes" : "No");

printf("Force: %s\n", opts.force ? "Yes" : "No");

// Validate option conflicts

if (opts.verbose && opts.quiet) {

printf("\nWarning: Both verbose and quiet specified\n");

}

// Process file with options

if (opts.verbose) {

printf("\nProcessing '%s'...\n", opts.inputFile);

}

// Actual processing would go here

if (!opts.quiet) {

printf("Done!\n");

}

return 0;

}

// Example usage:

// ./program input.txt

// ./program -v input.txt

// ./program -v -o output.txt input.txt

// ./program --verbose --force input.txt

// ./program -hBuilding a File Processing Tool

A practical file processing tool demonstrates complete argument handling including multiple files, options, and error handling. This example shows how to build utilities similar to common Unix tools like cat, wc, or grep.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

typedef struct {

int lineCount;

int wordCount;

int charCount;

} FileStats;

bool countLines = false;

bool countWords = false;

bool countChars = false;

void printUsage(const char *prog) {

printf("Usage: %s [OPTIONS] [FILE...]\n", prog);

printf("\nOptions:\n");

printf(" -l Count lines\n");

printf(" -w Count words\n");

printf(" -c Count characters\n");

printf(" -h Show help\n");

printf("\nIf no options specified, counts all.\n");

printf("If no files specified, reads from stdin.\n");

}

FileStats processFile(const char *filename) {

FileStats stats = {0, 0, 0};

FILE *file;

if (filename == NULL) {

file = stdin;

printf("Reading from stdin (Ctrl+D to end):\n");

} else {

file = fopen(filename, "r");

if (file == NULL) {

printf("Error: Cannot open '%s'\n", filename);

return stats;

}

}

int ch;

bool inWord = false;

while ((ch = fgetc(file)) != EOF) {

stats.charCount++;

if (ch == '\n') {

stats.lineCount++;

}

// Word counting logic

if (ch == ' ' || ch == '\n' || ch == '\t') {

inWord = false;

} else if (!inWord) {

inWord = true;

stats.wordCount++;

}

}

if (filename != NULL) {

fclose(file);

}

return stats;

}

void printStats(const FileStats *stats, const char *filename) {

if (countLines || (!countLines && !countWords && !countChars)) {

printf("%d ", stats->lineCount);

}

if (countWords || (!countLines && !countWords && !countChars)) {

printf("%d ", stats->wordCount);

}

if (countChars || (!countLines && !countWords && !countChars)) {

printf("%d ", stats->charCount);

}

if (filename) {

printf("%s", filename);

}

printf("\n");

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int fileCount = 0;

char *files[100];

// Parse arguments

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

if (argv[i][0] == '-') {

// Parse options

for (char *p = &argv[i][1]; *p; p++) {

switch (*p) {

case 'l':

countLines = true;

break;

case 'w':

countWords = true;

break;

case 'c':

countChars = true;

break;

case 'h':

printUsage(argv[0]);

return 0;

default:

printf("Unknown option: -%c\n", *p);

printUsage(argv[0]);

return 1;

}

}

} else {

// Add to file list

if (fileCount < 100) {

files[fileCount++] = argv[i];

}

}

}

// Process files or stdin

FileStats totalStats = {0, 0, 0};

if (fileCount == 0) {

// No files specified, read from stdin

FileStats stats = processFile(NULL);

printStats(&stats, NULL);

} else {

// Process each file

for (int i = 0; i < fileCount; i++) {

FileStats stats = processFile(files[i]);

printStats(&stats, files[i]);

// Add to totals

totalStats.lineCount += stats.lineCount;

totalStats.wordCount += stats.wordCount;

totalStats.charCount += stats.charCount;

}

// Print total if multiple files

if (fileCount > 1) {

printStats(&totalStats, "total");

}

}

return 0;

}

// Compile: gcc wordcount.c -o wc

// Usage examples:

// ./wc file.txt (count everything)

// ./wc -l file.txt (count lines only)

// ./wc -w file1.txt file2.txt (count words in multiple files)

// ./wc -lw file.txt (count lines and words)

// echo "hello world" | ./wc (read from stdin)Advanced Argument Parsing with getopt

For complex argument parsing, the getopt library function provides standardized option parsing following POSIX conventions [web:308]. It handles both short and long options, option arguments, and generates proper error messages, simplifying the development of professional command-line tools.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <getopt.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

// Note: getopt is available on Unix/Linux systems

// For Windows, consider using getopt-compatible libraries

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int opt;

bool verbose = false;

bool debug = false;

char *outputFile = NULL;

int level = 0;

// Define long options

static struct option long_options[] = {

{"verbose", no_argument, 0, 'v'},

{"debug", no_argument, 0, 'd'},

{"output", required_argument, 0, 'o'},

{"level", required_argument, 0, 'l'},

{"help", no_argument, 0, 'h'},

{0, 0, 0, 0}

};

// Parse options

int option_index = 0;

while ((opt = getopt_long(argc, argv, "vdo:l:h",

long_options, &option_index)) != -1) {

switch (opt) {

case 'v':

verbose = true;

printf("Verbose mode enabled\n");

break;

case 'd':

debug = true;

printf("Debug mode enabled\n");

break;

case 'o':

outputFile = optarg;

printf("Output file: %s\n", outputFile);

break;

case 'l':

level = atoi(optarg);

printf("Level: %d\n", level);

break;

case 'h':

printf("Usage: %s [OPTIONS] [FILES]\n", argv[0]);

printf("\nOptions:\n");

printf(" -v, --verbose Verbose output\n");

printf(" -d, --debug Debug mode\n");

printf(" -o, --output FILE Output file\n");

printf(" -l, --level NUM Set level\n");

printf(" -h, --help Show help\n");

return 0;

case '?':

// getopt_long already printed error message

return 1;

default:

printf("Unknown option\n");

return 1;

}

}

// Process remaining non-option arguments

printf("\nNon-option arguments:\n");

for (int i = optind; i < argc; i++) {

printf(" %s\n", argv[i]);

}

// Demonstrate parsed values

printf("\n=== Configuration ===\n");

printf("Verbose: %s\n", verbose ? "Yes" : "No");

printf("Debug: %s\n", debug ? "Yes" : "No");

printf("Output: %s\n", outputFile ? outputFile : "(none)");

printf("Level: %d\n", level);

return 0;

}

// Compile: gcc advanced_parsing.c -o prog

// Usage examples:

// ./prog -v file.txt

// ./prog --verbose --debug

// ./prog -o output.txt -l 5 input.txt

// ./prog --output=result.txt file1.txt file2.txtError Handling and Validation

Robust command-line tools validate all inputs, provide clear error messages, and handle edge cases gracefully. Proper validation prevents crashes, security vulnerabilities, and user confusion when arguments are malformed or missing.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <limits.h>

#include <errno.h>

// Validate integer argument

int validateInteger(const char *str, const char *argName, int *result) {

char *endptr;

errno = 0;

long val = strtol(str, &endptr, 10);

// Check for conversion errors

if (endptr == str) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: %s is not a number\n", argName);

return 0;

}

if (*endptr != '\0') {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: %s contains invalid characters\n", argName);

return 0;

}

if (errno == ERANGE || val > INT_MAX || val < INT_MIN) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: %s is out of range\n", argName);

return 0;

}

*result = (int)val;

return 1;

}

// Validate file path

int validateFile(const char *filename) {

FILE *file = fopen(filename, "r");

if (file == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Cannot open file '%s'\n", filename);

return 0;

}

fclose(file);

return 1;

}

// Validate argument count

int validateArgCount(int argc, int expected, const char *progName) {

if (argc != expected) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Expected %d arguments, got %d\n",

expected - 1, argc - 1);

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s <arg1> <arg2> ...\n", progName);

return 0;

}

return 1;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("=== Error Handling Examples ===\n\n");

// Example 1: Validate argument count

if (!validateArgCount(argc, 3, argv[0])) {

return 1;

}

// Example 2: Validate integer

int number;

if (!validateInteger(argv[1], "first argument", &number)) {

return 1;

}

printf("Valid number: %d\n", number);

// Example 3: Validate file

if (!validateFile(argv[2])) {

return 1;

}

printf("Valid file: %s\n", argv[2]);

// Example 4: Range validation

if (number < 1 || number > 100) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Number must be between 1 and 100\n");

return 1;

}

// Example 5: String validation

if (strlen(argv[2]) > 255) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Filename too long (max 255 characters)\n");

return 1;

}

printf("\nAll validations passed!\n");

// Best practices for error handling:

// 1. Check argc before accessing argv elements

// 2. Use strtol/strtod instead of atoi/atof

// 3. Check errno after conversion functions

// 4. Provide clear, specific error messages

// 5. Use stderr for error output

// 6. Return non-zero exit codes on errors

// 7. Validate ranges and constraints

// 8. Check file existence before processing

// 9. Handle NULL pointers

// 10. Test edge cases (empty strings, special characters)

return 0;

}

// Example usage:

// ./program 50 test.txt (valid)

// ./program abc test.txt (error: not a number)

// ./program 50 missing.txt (error: file not found)

// ./program 150 test.txt (error: out of range)Best Practices for Command-Line Tools

Professional command-line tools follow established conventions that make them intuitive, reliable, and composable with other utilities. Adhering to these practices ensures your tools integrate well into existing workflows and meet user expectations.

- Validate argc first: Always check argument count before accessing argv elements to prevent crashes [web:304]

- Provide usage information: Display helpful usage messages when arguments are missing or --help is specified [web:307]

- Use standard conventions: Follow Unix patterns: single dash for short options, double dash for long options

- Error messages to stderr: Print errors to stderr (fprintf(stderr, ...)) to separate from normal output

- Return meaningful exit codes: Return 0 for success, non-zero for errors (1 for general errors, specific codes for different failures)

- Support stdin when applicable: Read from stdin if no files specified, enabling pipe composition

- Use safe conversion functions: Prefer strtol/strtod over atoi/atof for better error detection [web:307]

- Handle edge cases: Test with no arguments, invalid arguments, special characters, and boundary values

- Document option arguments: Clearly specify which options require arguments (e.g., -o FILE)

- Make tools composable: Design for use in pipelines with other Unix utilities

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Not checking argc: Accessing argv[i] without verifying i < argc causes segmentation faults

- Using atoi for validation: atoi returns 0 for both valid "0" and invalid input—use strtol instead

- Forgetting argv[0]: Remember argv[0] is program name; user arguments start at argv[1]

- Modifying argv strings: argv strings may be read-only; copy to buffers before modification

- No usage information: Users get frustrated without help text explaining correct usage

- Silent failures: Always print error messages explaining what went wrong

- Inconsistent option format: Mixing different option styles confuses users

- Not handling special characters: File paths with spaces or special characters require proper handling

- Assuming argument order: Options and files can appear in any order; parse flexibly

- Poor error messages: Vague errors like "Error" don't help users fix problems

Conclusion

Command-line arguments enable C programs to accept input at launch through the main function parameters argc and argv, where argc (argument count) holds the total number of arguments including the program name, and argv (argument vector) is an array of string pointers with argv[0] containing the program name and argv[1] through argv[argc-1] holding user-provided arguments. All arguments arrive as strings requiring explicit conversion to numeric types using functions like strtol and strtod which provide error checking superior to atoi and atof that return zero for both valid zero and invalid input. Processing arguments involves iterating through argv, checking for option flags using string comparison, extracting positional arguments, and validating input before use to prevent crashes and security issues.

Building robust command-line tools requires implementing option parsing with both short (-v) and long (--verbose) forms following Unix conventions, providing comprehensive usage information with --help flags, validating argument counts and types before processing, writing error messages to stderr with specific descriptions of failures, and returning meaningful exit codes with zero indicating success and non-zero for various error conditions. Advanced parsing leverages libraries like getopt which standardize option handling, manage option arguments automatically, support option bundling, and generate consistent error messages. Best practices mandate checking argc before accessing argv elements to prevent segmentation faults, using safe conversion functions with errno checking, supporting stdin when applicable for pipeline composition, handling edge cases including empty strings and special characters, and documenting all options clearly. Common pitfalls include accessing argv beyond bounds without validation, using atoi which lacks error detection, forgetting argv[0] is the program name rather than the first user argument, modifying potentially read-only argv strings, providing no help text leaving users confused about usage, silent failures without error messages, and inconsistent option formats. By mastering command-line argument handling—from basic argc and argv access to sophisticated option parsing with validation and error handling—you build professional utilities that integrate seamlessly with shell environments, compose elegantly in pipelines, and provide the robust, user-friendly experience expected from quality command-line tools in the Unix tradition.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!