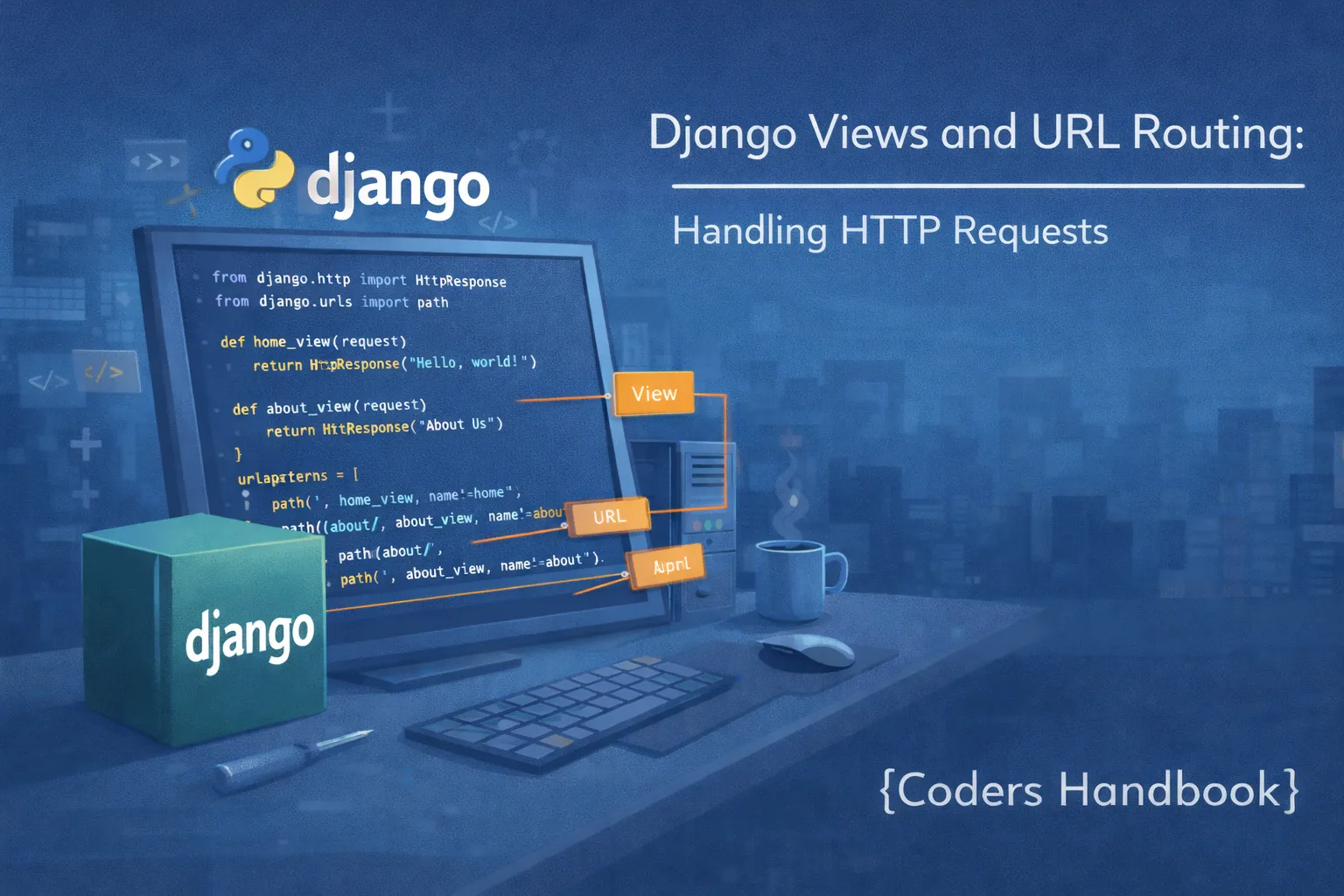

Django Views and URL Routing: Handling HTTP Requests

Django views form the core request-handling mechanism processing incoming HTTP requests and returning appropriate responses whether HTML pages, JSON data, redirects, or error messages. Views act as the controller in Django's MTV (Model-Template-View) architecture connecting models with templates, executing business logic, querying databases, processing form submissions, and implementing application functionality that users interact with through web interfaces or APIs. URL routing maps web addresses to specific view functions or classes establishing the connection between browser requests and Python code execution following Django's clean URL design philosophy that promotes human-readable, SEO-friendly URLs without file extensions or query string clutter. Understanding views and URL patterns is fundamental to Django development as every user interaction flows through this request-response cycle where URLs direct traffic to views, views process requests and gather data, templates render responses, and the cycle completes by delivering content to users. Mastering these concepts enables building dynamic web applications responding to user actions, displaying personalized content, handling form submissions, implementing authentication flows, and creating RESTful APIs serving mobile applications and JavaScript frontends.

Function-Based Views

Function-based views represent the simplest approach to handling HTTP requests in Django using regular Python functions that receive HttpRequest objects and return HttpResponse objects. These views provide explicit control over request handling making them ideal for straightforward operations like displaying static pages, processing simple forms, or implementing custom business logic that doesn't fit generic patterns. Function-based views accept the request parameter containing all request data including GET/POST parameters, headers, user information, session data, and cookies enabling complete access to incoming request details. Views return HttpResponse objects directly or use Django's render() shortcut combining templates with context data to generate HTML responses. The explicit nature of function-based views makes them easier for beginners to understand as the flow from request receipt to response return is clearly visible within a single function without inheritance or method resolution complexity found in class-based views.

# views.py - Function-based views examples

from django.shortcuts import render, redirect, get_object_or_404

from django.http import HttpResponse, JsonResponse, Http404

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required

from .models import Post, Category

# Simple view returning HttpResponse

def home(request):

return HttpResponse('<h1>Welcome to Django!</h1>')

# View using render() with template

def post_list(request):

posts = Post.objects.filter(status='published').order_by('-created_at')

context = {

'posts': posts,

'title': 'Blog Posts',

}

return render(request, 'blog/post_list.html', context)

# View with URL parameter

def post_detail(request, post_id):

post = get_object_or_404(Post, id=post_id, status='published')

related_posts = Post.objects.filter(

category=post.category,

status='published'

).exclude(id=post.id)[:3]

context = {

'post': post,

'related_posts': related_posts,

}

return render(request, 'blog/post_detail.html', context)

# View handling POST request

def create_post(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

title = request.POST.get('title')

content = request.POST.get('content')

post = Post.objects.create(

title=title,

content=content,

author=request.user

)

return redirect('blog:post_detail', post_id=post.id)

return render(request, 'blog/create_post.html')

# Protected view requiring authentication

@login_required

def dashboard(request):

user_posts = Post.objects.filter(author=request.user)

context = {'posts': user_posts}

return render(request, 'blog/dashboard.html', context)

# JSON response for API endpoint

def api_posts(request):

posts = Post.objects.filter(status='published').values(

'id', 'title', 'content', 'created_at'

)

return JsonResponse(list(posts), safe=False)

# View with multiple HTTP methods

def contact(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

name = request.POST.get('name')

email = request.POST.get('email')

message = request.POST.get('message')

# Process contact form

return redirect('contact_success')

return render(request, 'contact.html')URL Pattern Configuration

Django's URL configuration system maps URL paths to view functions using the path() function or re_path() for regular expression patterns. URL patterns are defined in urls.py files creating a urlpatterns list containing path definitions processed sequentially until a match is found. The path() function accepts three primary arguments: the route string defining the URL pattern, the view function or class to execute, and an optional name for reverse URL lookups enabling generation of URLs from view names rather than hardcoding paths. URL patterns support angle bracket syntax for capturing URL parameters like path converters including int, str, slug, uuid, and path types automatically converting captured values to appropriate Python types before passing them to views. Django's URL dispatcher stops at the first matching pattern making pattern order important where more specific patterns should appear before generic patterns to prevent incorrect matches. Understanding URL configuration enables creating clean, hierarchical URL structures, implementing RESTful API endpoints, handling dynamic content through URL parameters, and maintaining flexible URLs that can change without breaking links through named URL patterns and reverse resolution.

# urls.py - URL pattern examples

from django.urls import path, re_path, include

from . import views

app_name = 'blog' # URL namespace

urlpatterns = [

# Basic URL pattern

path('', views.home, name='home'),

path('posts/', views.post_list, name='post_list'),

# URL with integer parameter

path('post/<int:post_id>/', views.post_detail, name='post_detail'),

# URL with slug parameter

path('post/<slug:slug>/', views.post_by_slug, name='post_by_slug'),

# URL with multiple parameters

path('category/<slug:category>/post/<int:id>/', views.category_post, name='category_post'),

# URL with string parameter

path('author/<str:username>/', views.author_posts, name='author_posts'),

# Regular expression pattern

re_path(r'^archive/(?P<year>[0-9]{4})/(?P<month>[0-9]{2})/$', views.archive, name='archive'),

# URL with UUID

path('download/<uuid:file_id>/', views.download_file, name='download'),

# Catch-all pattern

path('page/<path:page_path>/', views.page_view, name='page'),

]

# Path converters:

# str - Matches any non-empty string excluding '/'

# int - Matches zero or positive integers

# slug - Matches slug strings (letters, numbers, hyphens, underscores)

# uuid - Matches UUID strings

# path - Matches any non-empty string including '/'

# Including app URLs in project urls.py:

# urlpatterns = [

# path('blog/', include('blog.urls')),

# ]HTTP Request and Response Objects

Django's HttpRequest object encapsulates all information about the incoming HTTP request providing access to request data through various attributes and methods. The request.method attribute contains the HTTP verb (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) enabling views to respond differently based on request type. GET parameters are accessed via request.GET dictionary, POST data through request.POST, uploaded files via request.FILES, and cookies through request.COOKIES. The request.user attribute provides the authenticated user object enabling permission checks and user-specific functionality. Session data persists across requests through request.session acting as a dictionary for storing user-specific information. HttpResponse objects represent the server's reply to client requests containing status codes, headers, and content. Django provides specialized response classes including HttpResponseRedirect for redirects, JsonResponse for JSON data, FileResponse for file downloads, and StreamingHttpResponse for large files. Understanding request and response objects enables extracting user input, managing sessions, setting cookies, customizing headers, handling different request methods, and implementing sophisticated request-response patterns required for modern web applications.

# Working with Request and Response objects

from django.http import (

HttpResponse, HttpResponseRedirect, JsonResponse,

FileResponse, Http404

)

from django.shortcuts import redirect

def request_example(request):

# Request attributes

method = request.method # GET, POST, PUT, DELETE

path = request.path # /blog/posts/

full_path = request.get_full_path() # /blog/posts/?page=2

# GET parameters: /posts/?category=tech&page=1

category = request.GET.get('category') # 'tech'

page = request.GET.get('page', 1) # Default value 1

all_get_params = request.GET.dict() # All GET parameters

# POST data

if request.method == 'POST':

title = request.POST.get('title')

content = request.POST.get('content')

file = request.FILES.get('document') # Uploaded file

# User information

if request.user.is_authenticated:

username = request.user.username

email = request.user.email

# Session data

request.session['views_count'] = request.session.get('views_count', 0) + 1

views = request.session.get('views_count')

# Cookies

theme = request.COOKIES.get('theme', 'light')

# Headers

user_agent = request.META.get('HTTP_USER_AGENT')

ip_address = request.META.get('REMOTE_ADDR')

# Response objects

# Simple HTTP response

response = HttpResponse('Hello World')

# HTML response with status code

response = HttpResponse('<h1>Not Found</h1>', status=404)

# JSON response

data = {'status': 'success', 'message': 'Data processed'}

return JsonResponse(data)

# Redirect

return redirect('blog:post_list')

# Or: return HttpResponseRedirect('/blog/posts/')

# File download

file_path = '/path/to/file.pdf'

return FileResponse(open(file_path, 'rb'), as_attachment=True)

# Set cookie

response = HttpResponse('Cookie set')

response.set_cookie('theme', 'dark', max_age=3600)

return responseURL Reversing and Named Patterns

Django's URL reversing enables generating URLs from view names rather than hardcoding paths promoting maintainability as URLs can change without updating code throughout the application. Named URL patterns use the name parameter in path() definitions creating unique identifiers for URLs that can be referenced in views, templates, and redirects. The reverse() function in Python code and url template tag in templates perform URL reversing accepting the view name and optional parameters generating the corresponding URL path. URL namespacing using app_name in app-level urls.py prevents naming conflicts when multiple apps have views with identical names requiring the namespace:view_name syntax for URL reversal. This approach separates URL structure from application logic allowing URL reorganization without breaking existing code, simplifies refactoring as changing a URL only requires updating one urls.py entry, and enables automatic URL generation for navigation menus, breadcrumbs, and links throughout templates. Understanding URL reversing represents professional Django development practices reducing maintenance burden and preventing broken links that damage user experience and SEO rankings.

# urls.py - Named URL patterns

from django.urls import path

from . import views

app_name = 'blog'

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.post_list, name='post_list'),

path('post/<int:pk>/', views.post_detail, name='post_detail'),

path('category/<slug:slug>/', views.category, name='category'),

path('create/', views.create_post, name='create_post'),

]

# In views.py - URL reversing in Python

from django.urls import reverse

from django.shortcuts import redirect

def create_post_view(request):

# Create post logic...

post_id = 123

# Generate URL using reverse()

url = reverse('blog:post_detail', kwargs={'pk': post_id})

# Result: /blog/post/123/

# Redirect using view name

return redirect('blog:post_detail', pk=post_id)

# Reverse with slug

category_url = reverse('blog:category', kwargs={'slug': 'technology'})

# Result: /blog/category/technology/

# In templates - URL reversing with {% url %}

# {% load static %}

#

# <!-- Simple URL -->

# <a href="{% url 'blog:post_list' %}">All Posts</a>

#

# <!-- URL with parameters -->

# <a href="{% url 'blog:post_detail' pk=post.id %}">Read More</a>

#

# <!-- URL with slug -->

# <a href="{% url 'blog:category' slug=post.category.slug %}">{{ post.category.name }}</a>

#

# <!-- URL with multiple parameters -->

# <a href="{% url 'blog:archive' year=2026 month=1 %}">January 2026</a>

#

# <!-- Using as template variable -->

# {% url 'blog:post_detail' pk=post.id as post_url %}

# <a href="{{ post_url }}">{{ post.title }}</a>View Decorators

Django view decorators modify view behavior adding functionality like authentication requirements, permission checks, HTTP method restrictions, or caching without duplicating code across multiple views. The login_required decorator restricts view access to authenticated users automatically redirecting unauthenticated requests to the login page defined in settings. The permission_required decorator checks user permissions ensuring only authorized users can execute certain views. The require_http_methods decorator limits views to specific HTTP methods like GET or POST returning HTTP 405 Method Not Allowed for other methods. Custom decorators can implement cross-cutting concerns like logging, rate limiting, or request preprocessing encapsulating logic that applies to multiple views. Decorators stack allowing multiple decorators on single views with execution order from bottom to top following Python's decorator syntax. Understanding decorators enables writing DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself) code extracting common functionality into reusable components, implementing consistent security policies across views, and maintaining clean view functions focused on business logic rather than infrastructure concerns.

# View decorators examples

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required, permission_required

from django.views.decorators.http import require_http_methods, require_GET, require_POST

from django.views.decorators.cache import cache_page

from django.shortcuts import render

from functools import wraps

# Require authentication

@login_required

def dashboard(request):

return render(request, 'dashboard.html')

# Custom login URL

@login_required(login_url='/accounts/login/')

def profile(request):

return render(request, 'profile.html')

# Require specific permission

@permission_required('blog.add_post')

def create_post(request):

return render(request, 'create_post.html')

# Raise 403 instead of redirecting

@permission_required('blog.delete_post', raise_exception=True)

def delete_post(request, pk):

# Delete logic

pass

# Restrict HTTP methods

@require_http_methods(['GET', 'POST'])

def contact(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

# Handle form submission

pass

return render(request, 'contact.html')

# Only allow GET

@require_GET

def post_list(request):

return render(request, 'post_list.html')

# Only allow POST

@require_POST

def api_endpoint(request):

# Process POST data

pass

# Cache view for 15 minutes

@cache_page(60 * 15)

def cached_view(request):

return render(request, 'cached_page.html')

# Stack multiple decorators

@login_required

@permission_required('blog.add_post')

@require_http_methods(['GET', 'POST'])

def admin_create_post(request):

return render(request, 'admin_create.html')

# Custom decorator example

def ajax_required(view_func):

"""Restrict view to AJAX requests only"""

@wraps(view_func)

def wrapper(request, *args, **kwargs):

if not request.headers.get('x-requested-with') == 'XMLHttpRequest':

return HttpResponseBadRequest('AJAX required')

return view_func(request, *args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

@ajax_required

def ajax_endpoint(request):

return JsonResponse({'status': 'success'})Error Handling and Custom Error Pages

Django provides mechanisms for handling HTTP errors gracefully displaying custom error pages instead of default browser error messages improving user experience and maintaining site branding during errors. Common HTTP errors include 404 Not Found when requested resources don't exist, 403 Forbidden when users lack permission to access resources, 500 Internal Server Error for unhandled exceptions, and 400 Bad Request for malformed requests. Django allows customizing error views by creating handler404, handler403, handler500, and handler400 variables in the root urls.py pointing to custom view functions. Creating custom error templates in the templates directory root named 404.html, 403.html, 500.html, and 400.html automatically renders these templates during respective errors when DEBUG is False. The Http404 exception can be raised explicitly in views to trigger 404 errors for specific conditions like invalid parameters or missing data. Understanding error handling enables creating professional error pages matching site design, logging errors for debugging, providing helpful error messages guiding users to correct actions, and maintaining security by not exposing sensitive information in production error messages.

# Error handling in views

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from django.http import Http404, HttpResponseNotFound, HttpResponseForbidden

from .models import Post

# Raise 404 explicitly

def post_detail(request, pk):

try:

post = Post.objects.get(pk=pk)

except Post.DoesNotExist:

raise Http404('Post not found')

return render(request, 'post_detail.html', {'post': post})

# Using get_object_or_404 shortcut

def post_detail_shortcut(request, pk):

post = get_object_or_404(Post, pk=pk)

return render(request, 'post_detail.html', {'post': post})

# Return 403 Forbidden

def delete_post(request, pk):

post = get_object_or_404(Post, pk=pk)

if post.author != request.user:

return HttpResponseForbidden('You cannot delete this post')

post.delete()

return redirect('blog:post_list')

# urls.py - Custom error handlers

from django.conf.urls import handler404, handler500, handler403, handler400

handler404 = 'myapp.views.custom_404'

handler500 = 'myapp.views.custom_500'

handler403 = 'myapp.views.custom_403'

handler400 = 'myapp.views.custom_400'

# Custom error view

def custom_404(request, exception):

return render(request, '404.html', status=404)

def custom_500(request):

return render(request, '500.html', status=500)

# templates/404.html

# {% extends 'base.html' %}

#

# {% block content %}

# <div class="error-page">

# <h1>404 - Page Not Found</h1>

# <p>The page you're looking for doesn't exist.</p>

# <a href="{% url 'home' %}">Go to Homepage</a>

# </div>

# {% endblock %}

# Settings for error pages to work:

# DEBUG = False

# ALLOWED_HOSTS = ['yourdomain.com']Views and URL Best Practices

Effective view and URL design follows established patterns promoting maintainability, security, and user experience. Keep views focused on single responsibilities avoiding god functions that handle multiple concerns splitting complex logic into helper functions or separate views. Use Django's shortcuts like render(), redirect(), and get_object_or_404() reducing boilerplate code and improving readability. Validate user input thoroughly preventing security vulnerabilities like SQL injection, XSS attacks, or unauthorized data access. Design RESTful URLs representing resources hierarchically like /posts/ for listing, /posts/123/ for detail, and /posts/create/ for creation following intuitive patterns users expect. Use slugs instead of numeric IDs in URLs when appropriate improving SEO and URL readability like /posts/django-tutorial/ instead of /posts/123/. Implement proper authentication and authorization checks ensuring users can only access permitted resources preventing security breaches. Return appropriate HTTP status codes like 200 for success, 404 for not found, 403 for forbidden, and 500 for errors enabling proper client-side error handling. These practices result in secure, maintainable views that scale from simple websites to complex enterprise applications.

$ share --platform

$ cat /comments/ (0)

$ cat /comments/

// No comments found. Be the first!